“Art brut is art brut and everyone has understood. Not quite well? Of course, that is why we are just curious to go and see.”

Jean Dubuffet

Every era has its share of misunderstandings and ignorance. One could write volumes on the history of the reception of art, point out countless examples of missed artistic encounters. There have been many mistakes, yet they should be pointed out with indulgence because we are certainly committing similar errors today. In his time Paul Vitry, the curator of the Sculpture Department at the Louvre, wrote about the possible acquisition of the Bois de la Maison du jouir by Gauguin: “The quality of these seems doubtful. I think we should thank the author for his proposal […] and refrain from it [1]”. More recently, this is what Alfred H. Barr, Jr., director of MoMA, answered on October 18th, 1956 to Andy Warhol who wanted to give the drawing entitled Shoe to the museum: “Regrettably, I must inform you that the committee decided [ …] not to accept it for our collection […] because of the drastic limitation of our galleries and our reserve capacity [2]”. Closer to the subject that concerns us here, we can note the blindness of the French cultural authorities unable to keep in France the collection of art brut assembled by Jean Dubuffet. Perhaps the countervailing power fighting the dominant ideology of the time were too weak to make accept a view that deeply questioned the way of perceiving art and the world. Are we more open-minded today? That is far from certain… During the exhibition devoted to Zdenek Kosek at the Palais de Tokyo [3] Bruno Decharme overheard one of the curators saying to the visiting journalists: “There is not too much of interest here …”! Move along, there is nothing to see here.

These few examples demonstrate the obvious fact that our perception and our aesthetic consciousness evolve over time and that we constantly discover artistic territories, previously invisible, depending on changes in cultural paradigms, or even scientific discoveries.

Repair History

The concept of art brut was born in a Europe devastated by World War II which had transformed the ideals of progress and humanism in genocidal impulse, into the radical destruction of reason. We might even be tempted to read art brut as the “return of the repressed”, the imagination’s response to normative science gone mad (of which Hiroshima constituted the peak); as a triumph of life over barbarism, as a way of warding off, somehow, the tragedy of Western culture. While art brut seems to bring some fresh air to centuries of convention and obscurantism, it nevertheless remains a black hole, with no possibility of clearly establishing its borders. But this is precisely what defines its strength and originality: we must accept that this territory of art and thought escapes us, haunts us, worries us and builds us all at once – a salutary guarantee of the freedom of the mind.

Jean Dubuffet wrote in August 1945: “I preferred ‘Art Brut’ instead of ‘Art Obscur’ [Obscure Art] because professional art does not seem to me any more visionary or lucid; rather the contrary. Long live fresh-drawn, warm, raw buffalo milk [4].” The artist is aware of the difficulty in defining his new concept but deflects potential criticism in a letter to Jean Paulhan, claiming that even if “a thing [is] indefinable, indescribable, elusive, this does not mean that it does not exist [5].”

Despite his initial wish not to define art brut, Dubuffet clearly delineated the artists he brought into his collection. According to him, art brut was a superior alternative to “cultural” art because of its originality: the “authors draw everything (subjects, choice of materials employed, means of transposition, rhythms, ways of writing, etc.) from their own depths. […] Here we are witnessing an artistic operation that is completely pure, raw, reinvented in all its phases by its author, based solely on his own impulses [6].”

Dubuffet chose to ignore contradictions and by coming up with the term “art brut”, like a magic wand, he shattered the concept of “art of the insane” that had been employed by his predecessors, psychiatrist-collectors and the Surrealists, two rival entities that he wished to overthrow. For him, all true creation originated in state of mind close madness; the distinction between art of the insane and art of the “sane” therefore had no reason to exist. He thus rejected the surrealist idealization of madness and transformed works created in the asylum, previously categorized as “psychopathological”, into works that existed outside of the psychiatric hospital. Choosing to ignore certain facts and highlight others, he minimized the notion of madness in the biographies he wrote. The Fascicules de l’Art Brut reveal his unconditional admiration for the creators of art brut and show his incredibly pertinent way of writing about their works. For example, he says the following about one of Jeanne Tripier’s embroideries: “We are accustomed to paintings which entail as a whole one single moment, while here [in Jeanne Tripier’s case] we are confronted with successive moments. […] We can hardly accommodate us such a new form of art in which the passage of time, rather than being implied, as is usually the case, and immobilized, continues to flow throughout the work and even constitutes its main source [7].”

Times have changed and the current team of the Collection de l’Art Brut continues to spread, to an increasingly broad public, the wealth of this thinking, which has however become problematic in light of the considerable expansion of the corpus, source of legitimate questions. Where is the boundary between “cultural” art and art brut? Many “professional” artists today do not hide the fact that they are self-taught, which does not diminish them in any way, on the contrary. Conversely, some artists associated with art brut have had academic education (Fernand Desmoulin, Louis Soutter, Carl Fredrik Hill and others). What, then, does “their own depths” mean? Furthermore, why did Dubuffet initially exclude non-Western creators of art brut? And how should we consider works produced in workshops for the mentally disabled that have nothing to do with the notion of clandestine production or artists’ rebellion against and rejection of society?[8] And what is behind the recent renewal in interest in these works? Has the inclusion of art brut in mainstream art exhibitions fundamentally changed the way institution look at these works? That is far from certain…

During his time as director of the Collection de l’Art Brut, Dubuffet’s spiritual son Michel Thévoz found a clever and spot-on way of avoiding the question of defining art brut by giving only indirect indications of a definition in order to promote the notion that the answer is not so simple. In his writings, he offers no lists of sociological criteria, nor satisfies the reader with binary oppositions, but suggests that art brut embraces a territory with blurred boundaries by playing with the word “rather”: art brut is to be found among the poor rather than the rich, among the old rather than the young, among women rather than men, among the insane rather than professional [artists], etc. It is a fundamentally orphan art, that is to say, free from any model, tradition or fashion […] an art indifferent to the applause of art insiders, originating in feverish mental state and from an almost autistic inner necessity [9]“.

Despite these difficulties, art historians as well as art lovers insist on identifying what unites these highly heterogeneous works that come from such diverse backgrounds and lack any formal similarities. Roger Cardinal thus applies himself to coming up with a list of formal approaches found in art brut [10]. For his part, Laurent Danchin differentiates, with disconcerting naiveté, the “false” clumsiness symptomatic of professional art from the “real” – which, in his view, is a way of recognizing true works of art brut [11]. It would seem that, from their point of view, the the main question was one of ”purity.” If, however, works of art brut have a specific quality then it has nothing to do with the “purity of culture” or “original purity” prior to any “mixing” – the Western fantasy aptly described by Serge Gruzinski: “Not only does no such thing pre-exist – even if this fantasy flatters our pre-occupation with authenticity and the obsessive fear of our origins – but everything indicates instead that the word ‘culture’ never covers a set fixed and precise borders [12].” The underlying issue would be primarily that of the supposed “model” (the primary culture or primary subject) and the “copy”, a basic principle relied upon by our Western metaphysical categorization [13]. Art brut shatters this principle and thwarts our illusions. Indeed, it compromises all identities and seemingly stable categories or definitions: art brut is a camouflaged revolt against the Lacanian concept of the Name-of-the-Father, against the exclusion of the eccentricity and differences under the pretext of a higher meaning of history.

How can we speak about art brut today?

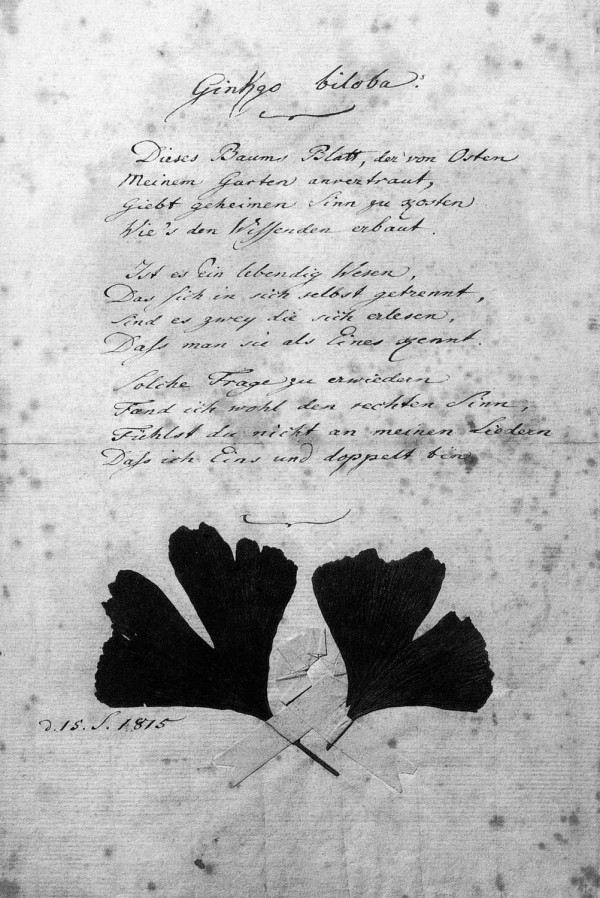

In light of these historical milestones we can see that in just a few years Dubuffet managed a truly personal revolution that led him from a primitivist reading of his first discoveries to a radically new point of view. His concept of art brut evolved with his collecting activities, his encounters with the artists and with intermediaries such as psychiatrists and other artists, and with his growing discovery of new works of art brut. In order to answer the questions posed above, we will thus need to look at the way in which the works in a collection are related. In Der Sammler und die Seinigen (The Collector and His Circle, 1799)[14], Goethe reveals some of his ideas on his collection, which was the true source of inspiration for his writings on the natural sciences and aesthetics. He writes about the morphological connection between things, the processes of the transformation of forms and the laws that govern them, the interrelationships that allow him to organize a mass of singular phenomena, and relationships based on “elective affinities” [15]. In a letter to Johann Gottfried Herder from 29 December 1786, Goethe wrote on the subject of art: “The ability to explore similar relationships, even if they are very distant from one another, and to have the intuition of the genesis of things, helps me also here extremely […] for me now, dear old friend, architecture, sculpture and painting are like mineralogy, botany and zoology[16].” According to Goethe, our senses, repeated contemplation with attention to detail, and renewed contact with the object are the safest way of gaining knowledge. The object contains an unknown law corresponding to an unknown law in the subject; it is an ontological structure, but also a mystery that leaves us stranded between recognition and not knowing, with the unlikely and profound union of disparate objects happening not on the visible level of their likeness, but at a deeper place, below the surface.

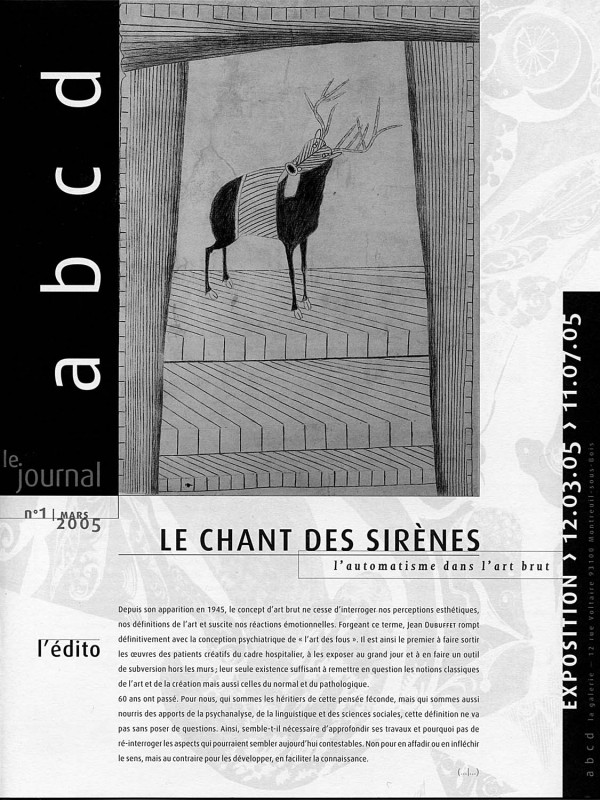

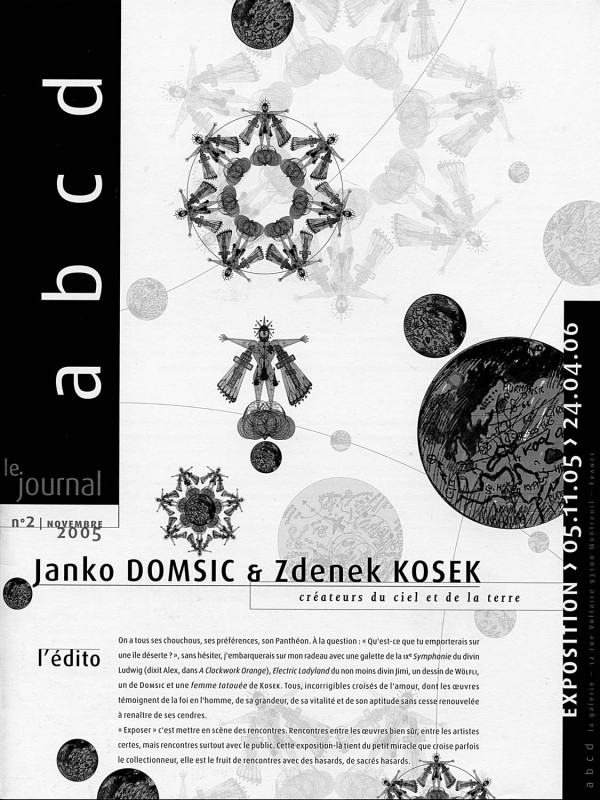

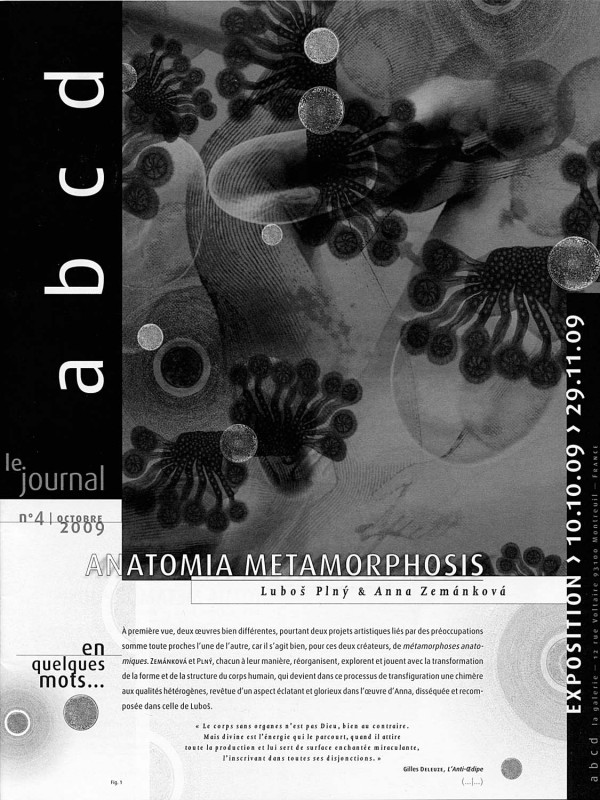

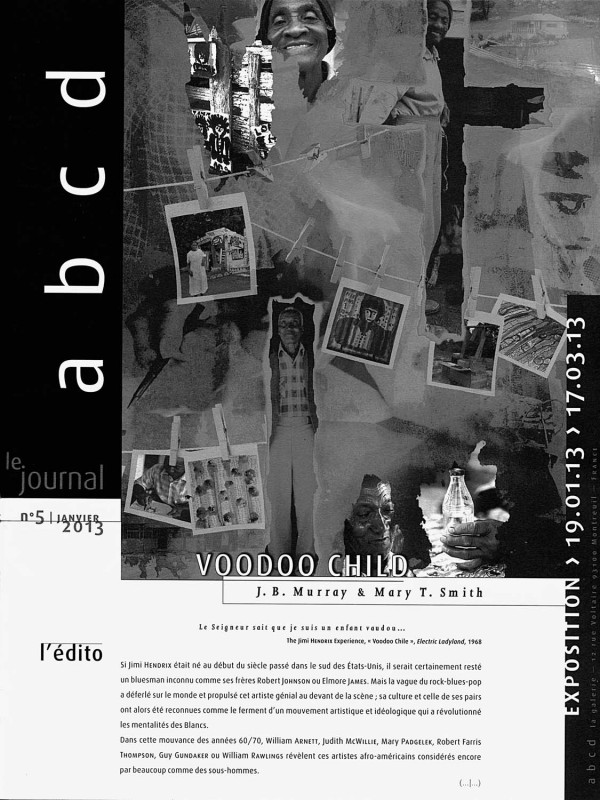

What, then, do the works in Bruno Decharme’s abcd collection have in common? The collection is closely related to the research that the collector wanted to initiate by creating the association. Since its foundation in 1999, its members participate in the adventure of the exploration of art brut and develop their work in parallel to the collection and its evolution. The catalogue documenting the exhibition of the collection in L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue [17] presented the first attempt at analysis of the works, following the principle of the alphabet: a non-hierarchical way of treating the subject, with no pretention at any dogmatic interpretation, as can be seen from the titles of some of the articles: “Body Art”, “Brut Bricolage”, “Graffiti”, “Ear Upside Down”, “Puzzle”, “Front and Back”, etc. However, thinking about art brut would be impossible without the discovery of new works and by the inclusion of new artists in the collection. The abcd space in Montreuil has thus shown a number of artists – or at least some aspects of their work -, unknown to the French public: the Czechs Zdenek Kosek, Lubos Plny and Anna Zemankova, the Croatian Janko Domsic [18]. The exhibition of some artists from the Creative Growth Art Center (Dwight Mackintosh, Dan Miller, Donald Mitchell, Aurie Ramirez, Judith Scott [19]) questioned the creative process in a workshop setting. Le chant des sirènes: l’automatisme dans l’art brut [The Song of Sirens: Automatism in Art Brut] [20] attempted to explore the aesthetic aspects of the automatic mental mechanism that characterizes the work of certain creators of art brut, dictating recurring patterns or associations. Finally, the corpus of art brut has been also enriched by non-Western works, at the crossroads of several cultures, which have enriched and questioned the concept. This has been shown by the exhibition Voodoo Child: J.B. Murray and Mary T. Smith in 2013, featuring works of two African-American artists from the South, heirs of the uprooting induced by the slave trade. One of the important questions remains how to exhibit these works. Do they communicate with the works of contemporary artists? And if yes, how? The exhibition De la lenteur avant toute chose [21]… [About Slowness First and Foremost…] offered a possible answer, having chosen the aspect of the “slowness” of the creative process, bringing together works that all reflect the experience of duration, expanding the present, the infinite repetition of the lived moment.

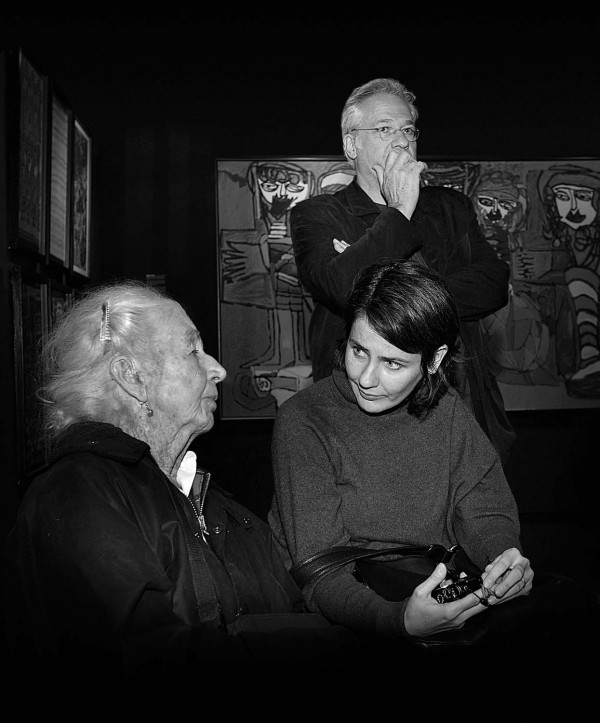

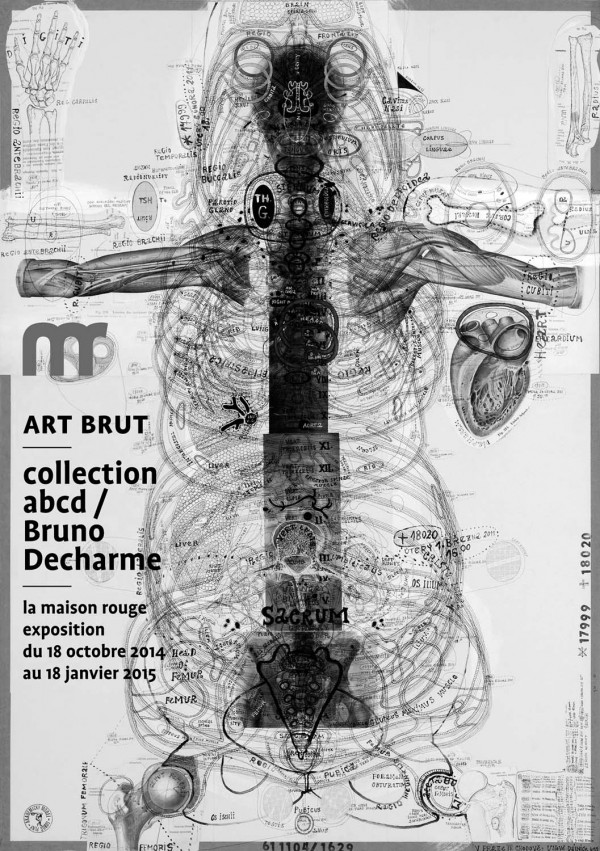

By exhibiting at La maison rouge, Bruno Decharme wanted to propose another reading of art brut, reach a different audience than the usual visitors of art brut exhibitions. The exhibition design and itinerary were also intended to avoid the habitual, potentially dated connotations. By accepting the invitation from a space dedicated to contemporary creation, the objective was to show that art brut is part of our culture and of the history of art, that defending it does not mean consigning it to an artistic ghetto but on the contrary, put it into the spotlight and give it the place it deserves. And by inviting publication contributors from diverse backgrounds, we chose a kaleidoscopic way of apprehending the field, as interdisciplinary approach seemed essential to us to address these works in all their complexity.

Numerous projects and exhibitions from recent years testify to this will to open up art brut to broader audiences; the donation of the collection of the l’Aracine to LaM in Villeneuve d’Ascq, alongside modern and contemporary art, is one example. The 2013 Venice Biennale, which received extensive press coverage, surprised the public by showing many works of art brut. Are we moving in the right direction? Some disgruntled spirits persist in prefering marginality. Yet for abcd art brut is part of the history of mankind; it is undoubtedly one of its finest treasures, which should be shared, provided we take some precautions. We should remember that most of these works testify of an attempt to repair and rescue. How to reclaim one’s land, one’s body? Repair, heal, protect. “Repair the fault”; this is what Adolf Wölfli writes: “Full of sadness, remorse, pain, nostalgia, fear and grief, it has been already fourteen years that I have been spending my miserable life behind the locked door of an asylum cell = of the alienated at the Waldau: a truly unfortunate accident that I am unable to fix a mistake I made, I have been obliged to leave all my relatives as well as my poor beloved and abandon her to capricious foreign elements[22].” Do the creators of art brut wish to rewrite, repair history? But which history? Theirs ? That of the world? Or both, in a kind of entanglement impossible to unravel?

“Art Brut is art brut and everyone understood very well [23]“? Nothing is clear and that is why we must go to see… Observe each work patiently, silently, let oneself be enchanted by it.

[1] Archives of the Louvre, Paul Vitry, October 6th, 1932, answer to the sale proposal of Gauguin’s woodcuts to the Louvre by Amédée Schuffenecker – brother of Gauguin’s friend.

[2] Archives of Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, translation Barbara Safarova.

[3] “Je suis le cerveau de l’univers.” Zdenek Kosek was one of the exhibitions organized for the re-opening of Palais de Tokyo in 2012.

[4] Jean Dubuffet, letter to René Auberjonois, Lausanne, August 28th, 1945, in Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, Paris, Gallimard, 1967, vol. II, p. 240.

[5] Id., letter to Jean Paulhan, November 7th, 1945, in Jean Dubuffet, Jean Paulhan: correspondance 1944-1968, Paris, Gallimard, 2003, p. 249.

[6] Id., “L’art brut préféré aux arts culturels” [1949], in L’Homme du commun à l’ouvrage, Paris, Gallimard, 1973, p. 91-92.

[7] Id., “Messages et clichés de Jeanne Tripier la Planétaire”, in L’Art Brut, no. 8, Paris, Compagnie de l’Art Brut, 1966, p. 28.

[8] Yet Dubuffet’s position seems clear when he writes that “in art therapeutic workshops the aim is to bring, as elsewhere, the patient to commonly accepted conventions, and therefore this is an action performed inversely to the production of art brut that it implies the negation of accepted conventions, based on refusal and insurrection.” (Id., “Au Dr Jean Benoiston”, April 24th,1963, in Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, op. cit., vol. IV, no. 58, p. 573.

[9] Michel Thévoz, Requiem pour la folie, Paris, La Différence, 1995, p. 49.

[10] Roger Cardinal, “Toward an Outsider Aesthetic”, in Michael D. Hall & Eugene W. Metcalf, Jr. (ed.), The Artist Outsider: Creativity and the Boundaries of Culture, Washington & London, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

[11] Laurent Danchin, “L’art brut à l’ère de la com: quels critères? quelles définitions?”, conference entitled “De quoi la contre-culture est-elle le oui?”, Paris, Maison des cultures du monde, June 22nd, 2013.

[12] Serge Gruzinski, “Planète métisse, ou comment parler du métissage”, in Planète métisse, exh. cat., Paris/Arles, musée du quai Branly/Actes Sud, 2008, p. 17.

[13] Gilles Deleuze, “Simulacre et philosophie antique”, in Logique du sens, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1969, p. 292-324.

[14] J. W. von Goethe, Le Collectionneur et les Siens, annotations by Carrie Asman, translated by Denise Modigliani, Paris, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1999.

[15] Die Wahlverwandtschaften, is the title of Goethe’s novel whose narrative is built on a chemical analogy: the attraction of certain substances to others. In this expression of “elective affinity” appears both the idea of irresistible attraction, but also of selective preference.

[16] Letter of J. W. von Goethe to J. G. Herder, December 29th, 1786, in J. W. von Goethe, Goethes Werke (“Weimar edition”), 143 vol., Weimar, H. Böhlau, 1887-1919, repr. Munich, 1990, IV, 8, p. 108 and 110.

[17] Folies de la beauté, exh. cat., Arles, Actes Sud, 2000.

[18] Anatomia metamorphosis: Lubos Plny and Anna Zemankova (2009) and Janko Domsic and Zdenek Kosek: Creators of Heaven and Earth (2005).

[19] Montreuil California (2007).

[20] Inaugural exhibition of the abcd space in Montreuil (2005).

[21] Exhibition organized by the association Portraits (2013).

[22] Adolf Wölfli, in Adolf Wölfli Univers, exh. cat., Lille, LaM, 2011, p. 43.

[23] J. Dubuffet , “L’art brut”, in L’Homme du commun à l’ouvrage, op. cit., p. 84.