At the end of the war, in 1945, Jean Dubuffet outlined the contours of the concept of art brut. At the same time, in the psychiatric hospital where he ended after an acute psychotic episode, Serge Sauphar, age twenty-six, found an isolated corner to house a creative activity that would continue during the forty years of his final hospitalization. He was concerned with no aesthetic purpose. He addressed the “medical profession”: “I want to let you know that I do not consider the work I perform as a work of art but only as having a definite purpose: namely to be helpful to the medical profession. […] In any case the works given to the doctors cannot get out of their hands.” His work is therefore a contribution to medical knowledge – aimed at developing it. Strange knowledge, ineffable, originating at the heart of intense perplexity of a night of anguish which he can only leave behind to become a living dead in the hospital, his “desert island”: “I cannot make myself understood. […] I have dived into the world of perdition of being […] psychological and psychoplasmic heartbreak.”

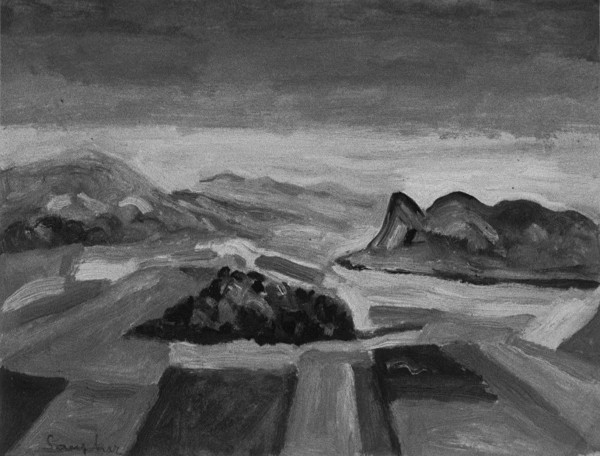

Similarly to the ego, reality disintegrates into a twilight world in which the landscape loses the memory of life, to become a rigid and geometric fossil (Fig. 1, 2, 3).

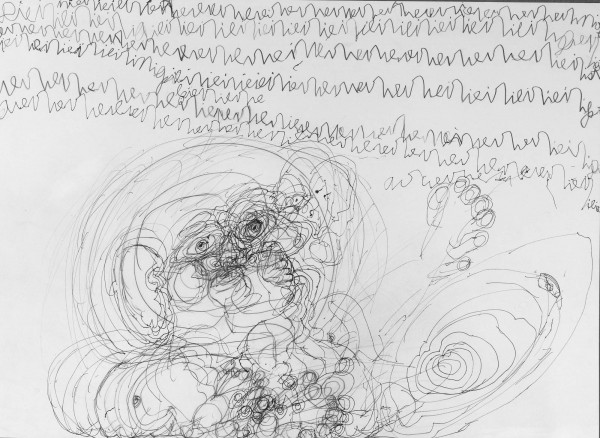

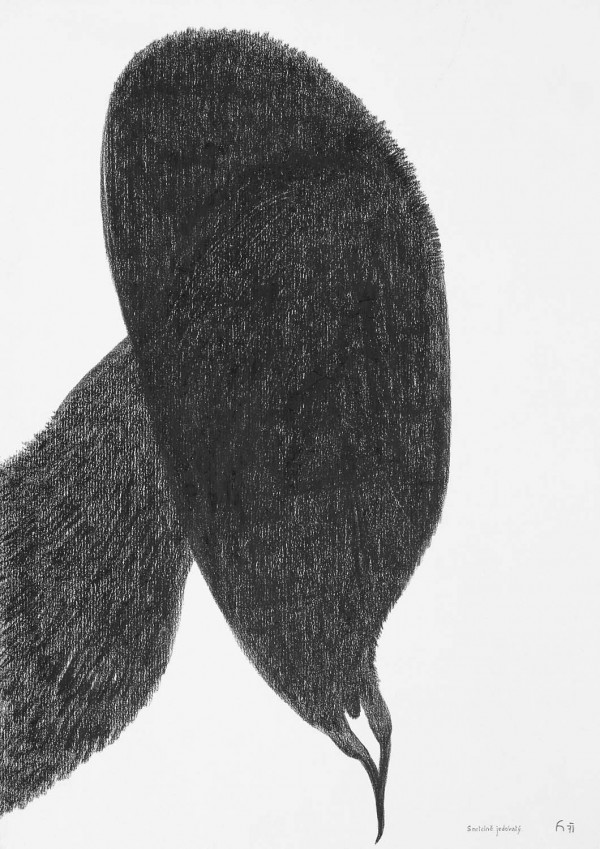

He paints, draws and writes tirelessly – by necessity, he says – seeking to contain complex mental states. He tells us of the terrible night of anguish during which he felt bewitched, split, cut off from the human world: “I saw the Furies appear […] I experienced the horror of infernal sensations invading my brain, the fusion-dissolution of my being.” His “poissons insolubles” [literally “unsolvable fish”; reference to the text by André Breton entitled “Poisson soluble”], trapped in a “mère océanique” [”oceanic feeling” – the feeling of oneness; “mère” – mother; “mer” – sea] transform the allusion to Breton to a more personal cause (Fig. 4)!

And the bird crucified at the feet of the sea shell Queen of the Night, does it not show the impossible birth, the impossible flight of a bird which has become a Christ-like sacrifice (Fig. 5)?

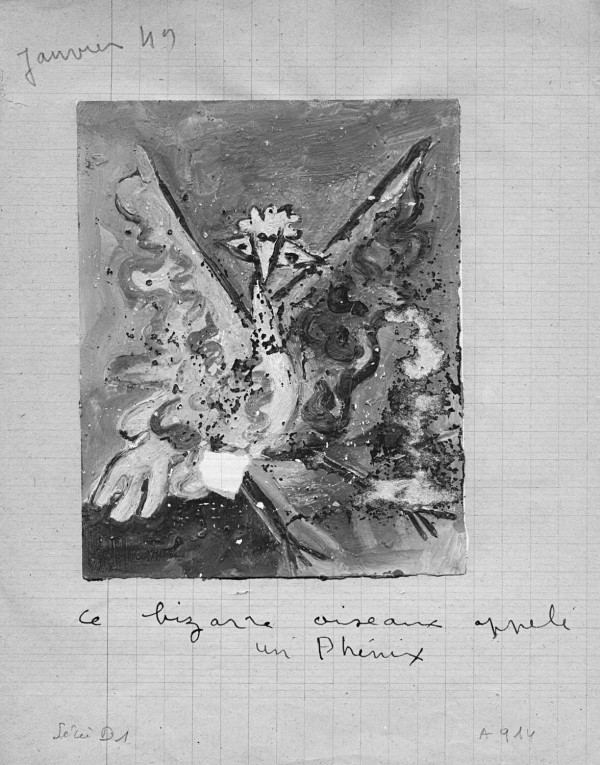

He entrusts his body-object – object-painting – to the medical profession requesting to keep it and extract knowledge from it. In this way he can be indefinitely reborn similarly to “the strange bird called Phoenix” (fig. 6), unable as he is to take up his place as a subject – becoming, for example, an artist.

What a “strange bird” indeed, demanding us to receive him as a subject “subjected to”! And by means of a paradox that looks like a stroke of genius, he obliges us at the same time, through his work, to maintain him “inalienable” – for eternity because the “medical profession” to which he offers himself is a permanent institution.

Is this art?

The knowledge we are dealing with here originates in artistic objects representing the complexity of “mental reality,” another scene where dreams are being elaborated – and also occasionally delusion – revelations of an elsewhere of ourselves that we can only consider as strange. We can say about it the same thing as about a dream that it is weird – without ignoring it harbors a repressed truth.

Because what makes us stop in front of some of these images, is not only our attraction to the exoticism of the odd or the quaint. It is the encounter with a find that hits the mark giving formal consistency to a hidden problem.

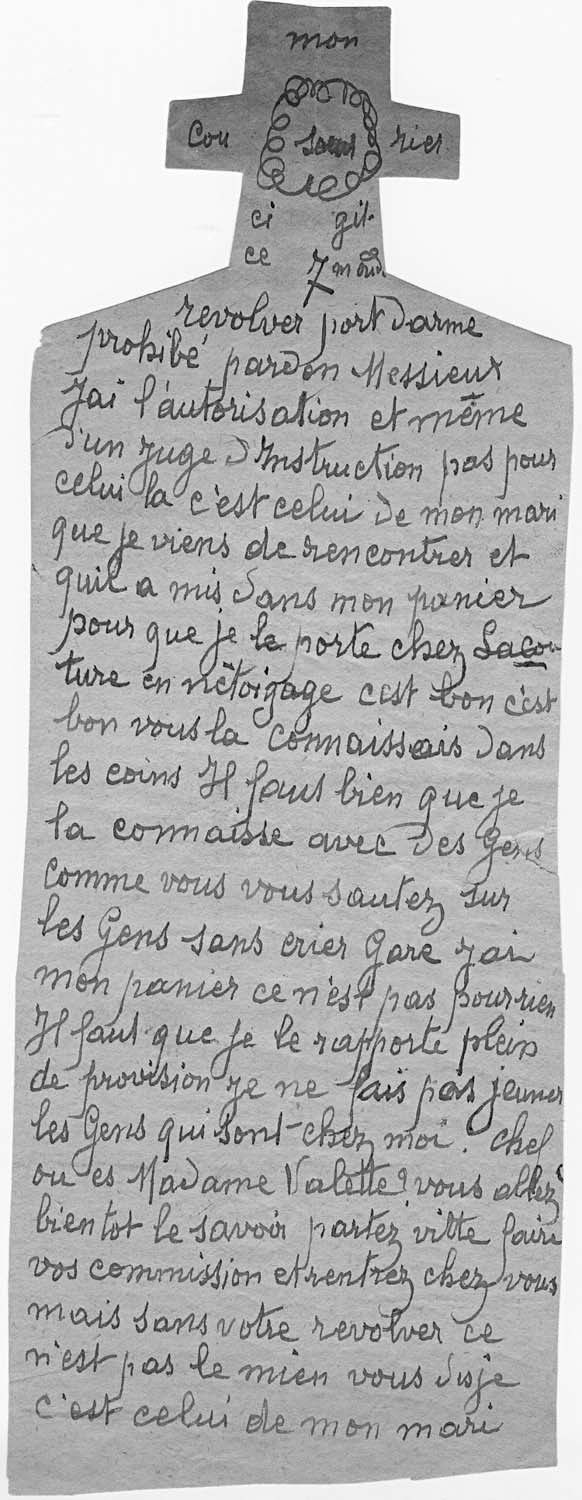

Can we look at the letters signed by Sister ci-gît ce Monde [here lies the World], enclosed in the form of a headstone, without being confronted with the question of death (fig. 7)?

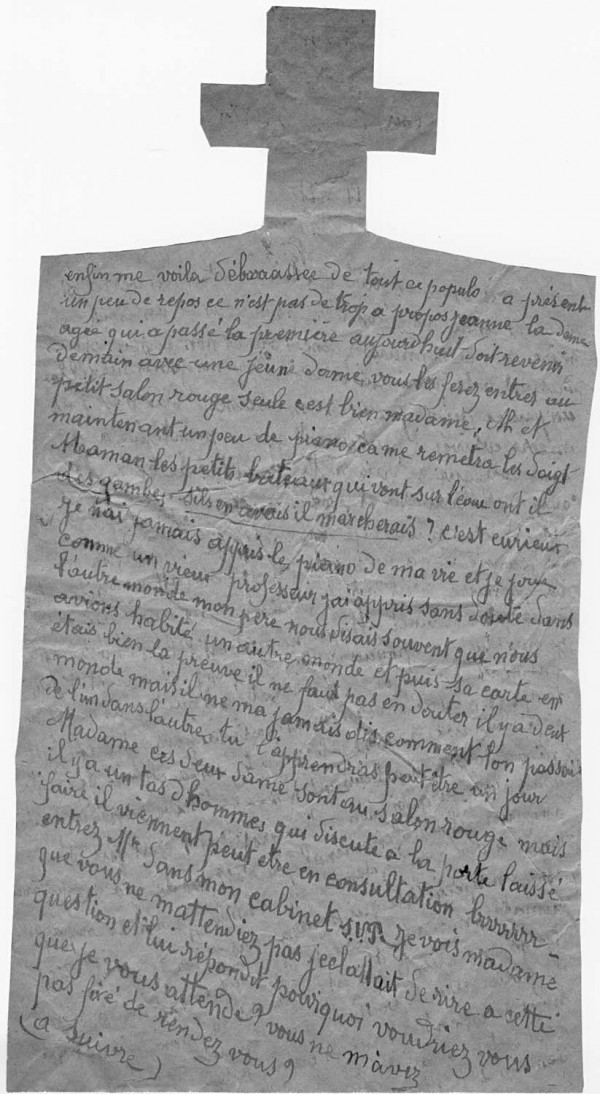

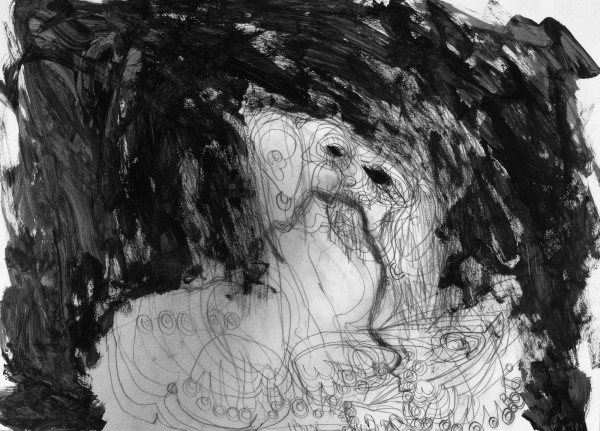

Originating beyond common sense, as a call for help when facing a global catastrophe, these letters confront us with an invasive imaginary aberration, with the obscure yet familiar sensation of the shift towards the possibility of death: the tomb has been open for us since the very beginning. And it is from the depths of repression salutary for our survival that we receive the delusional irony that, against all reality, prefers the collapse of the world to our inevitable end (Fig. 8).

Aesthetics of intimacy where the encounter is about the clash of subjectivities: the adjustment of representation to fit the mental reality of an author happens to reveal a little-known psychic content in the viewer. The latter suddenly struggles with the nonsense of formal discovery that condenses the form of the grave with the writing of the letter – and confronts him, with the same brutality, with the habitually repressed knowledge of his announced death.

In this encounter there is no real sharing, but rather a kind of overlap: the viewer cannot identify with the mental reality of the author but he recognizes something that it is not completely foreign. As for the author, he does not seek any communication with others, he only works at explaining what threatens him, and finds in representation, which puts some distance between him and an unbearable personal experience, a means to calm his anxious perplexity – unless he works under the compulsion of hallucination, representing what torments him.

But is there then, in the mental structure, something that drives u to produce images?

The creation of images is at the origin of all cultures. And if we find those created by prehistoric man deep in caves, it is not only because they were protected there, but also because someone put them there.

Every human being goes through, a time at least, the production of images. For some this activity persists throughout their life, others discover or rediscover it only at some specific moment. For all, creating images is a compelling inner necessity that imposes itself.

A necessity, does it mean something that does not cease [“qui ne cesse pas”]?

This leads us to ask our question differently: how does human subjectivity constitute itself, and what is the function of creating images in this process?

My hypothesis has the form of a story that is not a chronological history; it is a simple logic reconstitution, a kind of tale that has the form of a narrative for the sake of convenience. I imagine that it happened that way.

After nine months of a life underground – underground life that justifies perhaps the presence of images in the caves of our prehistory, a child comes into the world.

The child is a premature being, immediately taken, carried, fed, but in a state of total dependence, threatened by physiological distress at the slightest abandonment. Its motor incapacity shows its restless reflex movements. It is left without recourse to a kind of perceptual cacophony: the external sensory perceptions mingle with internal sensations without the possibility to distinguish between an outside and an inside (Fig. 9). Its cries and outbursts testify of its dramatic situation, its happy smile of some peace. The first episode, which should not leave us only with good memories were we judge by the fear aroused by the slightest limitation of our independence, any sensory deficit that would leave us to a similar dependence.

Thus all human life begins with being an object: object of care, certainly attentive most of the time, but nevertheless an object, subjected to a hold of which we do not know in advance the intention – beneficial or harmful. It is in the mystery of that intent that we are growing up with as the only point of reference the good or bad sensations of the body, without any perceptual discrimination at this stage.

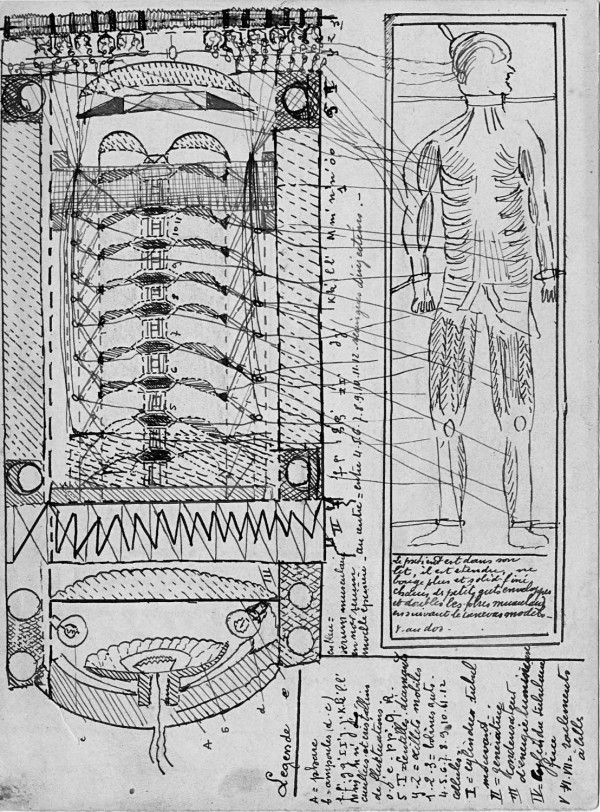

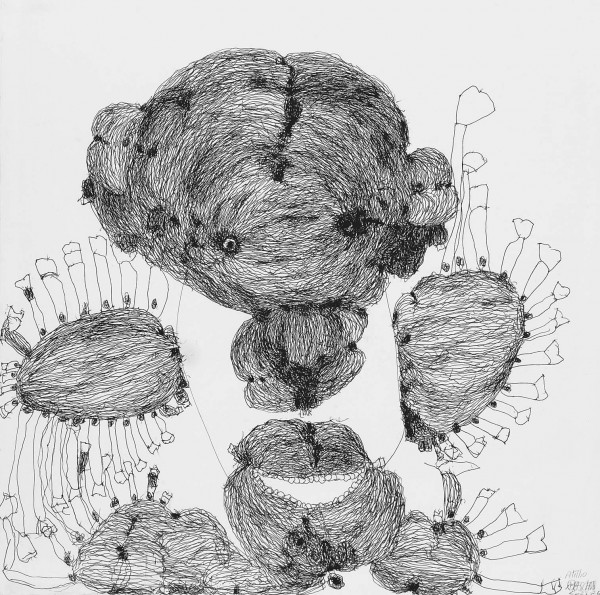

In this period of immaturity, the subject senses a struggle, governed by an intention he supposes, because of this sensation of struggle. So when an anonymous creator presents his delusional equipment, an influencing machine, we have no trouble identifying it as an infernal plot (fig. 10).

In the chaos of sensory perceptions two successive miracles will occur. No one knows how this is possible. We only know that sometimes miracles do not happen.

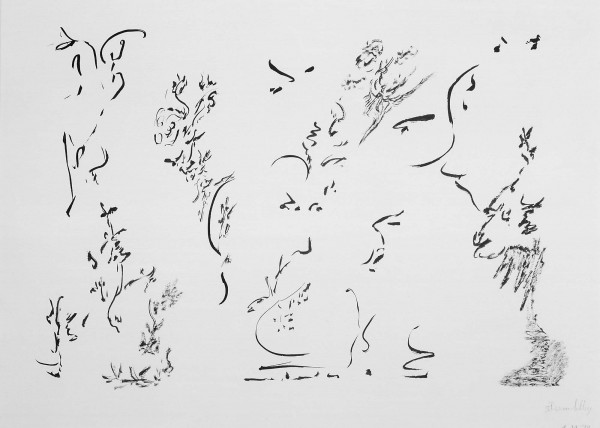

Amid a sensory overload from everything that is going on around and above its crib, amid the torment caused by the internal tensions of the body, something emerges: there are sounds, noises and some are recognized as sounds articulated together (fig. 11). Miracle: the child recognizes that these are articulated sounds of language. Otherwise the only possible destiny is death: how to survive without any perceptual discrimination?

Of course it cannot in any way identify from where these sounds come; while it has already heard or felt them from the depth of its uterine and marine life, they are now different because of being transmitted and received in the air.

“It” speaks! I say “it speaks” because language somehow falls on the child surrounded by the sounds without an identifiable place of enunciation.

A second miracle will then occur. It is expected by all mothers who watch out for the first “real” smile of their child; this language coming from elsewhere is directed at it! Not only does it speak, but it speaks to it. If everyone is worried when the child does not “really” smile it is indeed because the second miracle has not happened. That means that the child is condemned to wandering in a constellation of signifiers. While “it speaks”, it does not concern it. This is the stellar destiny of an autistic child: it is like a cosmonaut who had escaped the earth’s attraction, doomed to wander around the stars (fig. 12).

Most of the time the two miracles occur: the articulate sounds of language are identified in the perceptual magma: it speaks and above all, it speaks to me! An intention that concerns me emanates from the language. That is why we suppose that language desires us. So we suppose there is a carrier to this desire, to this intention. We are dealing here with a grammatical subject only, purely supposed. At the beginning was the Word.

If it speaks to me is then it means it wants something from me, and it lacks something because it wants it. Thus, in the heard language, a request is articulated, originating in faceless elsewhere, without a determined place of enunciation at this stage, and from which emanate the articulated sounds of language.

But what does it want from me?

We constantly ask ourselves: what are we here for? Where is our vocation? And the word vocation does refer to something that should be heard. For some, the answer is the call of God, an enigmatic appeal par excellence, but having the advantage of resolutely placing this request in inaccessible mystery.

And if it were the whole me who was the subject of this request (fig. 13)? Since its early experience of being manipulated in all ways, our infant may feel that the dark forces want to seize him. Besides, when we no longer know which way to go, we call ourselves “lost”; that is to say how strong is the temptation to protect ourselves from the abandonment by responding to this request, even if we believe it tyrannical, by the pure and simple offering of our whole body – with the risk of losing ourselves! And is that not exactly what happens in a turmoil of passion when, “madly” in love, for example, we abandon ourselves entirely.

Let’s summarize the steps in the formation of primal fantasy.

They are logical, not chronological: it speaks, it speaks to me, it wants me. I offer my body to satisfy this supposed demand, which is also the promise of enjoyment, enjoyment of profusion, making us “burst into tears” when for example unexpectedly reunited. But this enjoyment of fusion would be prohibitively expensive were it realized “for good” because in such arrangement, the child would find itself in sacrificial position, in the position of an object offered to a faceless greed, similarly to what we feel when we are afraid of being “attracted” by the vacuum. The term of attraction implies an intention, a “presence”, however improbable at the bottom of this void (fig. 14).

Between the abyss and the ogre, this is what haunts all our nightmares: an enigmatic intention leading the subject to lose himself. Generally we forbid ourselves access to the enjoyment of a deadly reunion … by waking up! We still have an ideal of being complete that is fulfilled in the hope of “becoming one” through the romantic encounter for example. But we are not yet there.

Our baby has grown. It has become able to recognize the people around it and to identify who is speaking. Articulated sounds of language are spoken by someone, a person, and the baby recognizes this other has a face.

Better yet it can perceive itself as a separate subject (fig. 15). Recognizing in the mirror the person carrying it, it recognizes itself gleefully, discovering the virtual control of being able, at will, animate the image that moves thanks to its own movement and perceive the pieces of its own self. In the motricity of the act of painting, we can find something similar to that moment of discovering itself in the mirror.

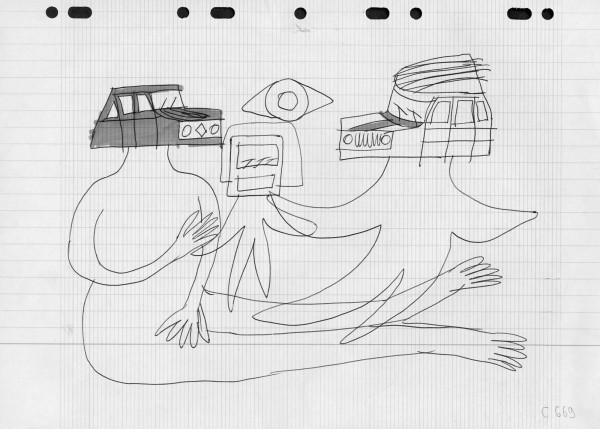

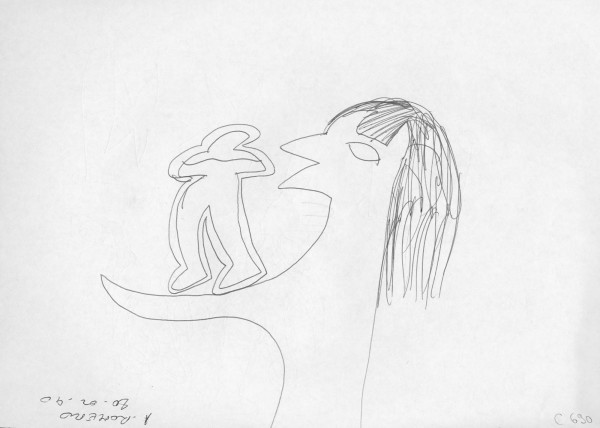

One would hope that the identification of the place of enunciation will allow the child to understand that the language it heard in its crib without knowing where it came from was, in fact, the same it sees now spoken by those around it. Essentially its mom and dad, disregarding whether their representation is “angelic”, tricky or composite (Fig. 16). Unfortunately this is not what happens!

In fact, this is what it tells itself: now that I see Mom and Dad who speak to me, who was “the one” who spoke to me “before” at the time of the bottom of my crib when I felt surrounded by an intention without face (fig. 17)? Retroactively, it can give anthropomorphic consistency to the enigmatic intention it felt; and, conversely, ask itself which intention hides behind every face it sees, behind every reality.

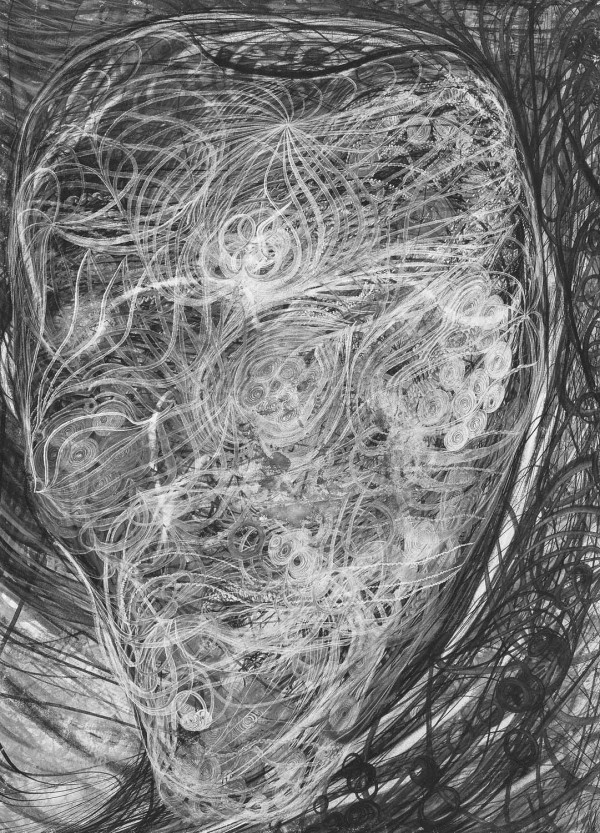

This is because every step of our life remains registered on one of the stratified layers of our memory (fig. 18). Each time we interpret retroactively the previous. But at all times the oldest memory remains registered and can resurface, upsetting our perception of reality.

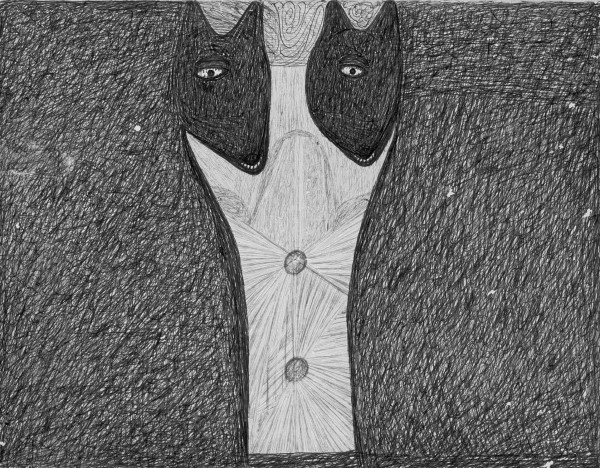

That is why starting from the mirror stage there is a ghost in our subjectivity whose face we will never cease to search for, making the fortune of all wolves and other bogeymen, all heroes facing doom and all suspense scenarios for a very long time (fig. 19). This ghost is the other, imagined retroactively, a pure logical effect: the elusive subject of the supposed desire of language – and who will never coincide with any of the people we will encounter.

As we will never solve the enigma of his demand, the unanswered question will always be there: what does he want from me?

Probably not anything good (fig. 20)! That is why we will have to organize our defense and resist his deadly appeal. To shield ourselves – not least by the double outline of an image – against the temptation to cede to his call threatening to engulf us. To represent is already putting a distance between us and the threat, this dark reality that disturbs our apprehension of the outside world.

Creating images is thus linked to a defense strategy. In fact, it is a practical joke: the perceived threat, the call to sacrifice ourselves are only imaginary since they emanate from an instance that is a mere assumption!

The primal fantasy is a platform common to all of us, it will however experience different fates.

The primal fantasy is a complex process, a sort of myth of individual origins, which keeps the trace of each particular development, a “forgotten” history, repressed deep within us. It refers to a kind of prehistory of the subject that does not fit into accessible memory, yet constitutes the matrix of our sensitivity and our whole personality.

Freud said that the primal repression does not repress anything – we should complete his sentence: it is the repression of nothing else but an assumption!

The history of the subject will be built on the walls of this repression, and each stage of the story might, in the secrecy of the unconscious, reactivate segments of his prehistory.

There are two situations in which repression no longer works: in anxiety, the feeling of danger is very real though not identified; and in hallucination, the certainty of a strange voice, heard “in the head”, is total.

Most of the time, the repression of primal fantasy is very strong. For those who will become “artists” a process of sublimation will take place, under the protection of culture, which is our collective rampart. Creative activity becomes part of an aesthetic purpose – a way to meet the supposed calling. But without losing oneself!

For others, making images will become a disposable device or erosion of primal fantasy. The time of life when this activity is triggered is important. A trigger is necessary and it is unpredictable. Such individuals will need to defend themselves in a specific one-on-one and they will begin producing images which we call art brut.

In art brut an image demonstrates -on could say testifies – to an elusive mental reality. A strange transparency, one could say a “transparure” makes it irreducible to its sole surface. It puts into perspective this unrepresentable territory of archaic enunciation which places us permanently in the assumption of being surrounded by an intention.

An image is then a transfer and adornment at the same time: it gives shape to the intention to which we feel subjected, dressed as an ornament to escape the horror of emptiness, or the monster. Dangle something where there is nothing to seize except an existential threat which the creation of images is likely to mediate.

Art brut tells of a story without words, a time when sensory experience could only be registered “brutally”, that is to say as a trauma the repression of which would absorb these persistent first impressions. In our memory, there remain only its traces: art brut sometimes rings the bell, raises a corner of the veil by which they are usually covered. Art brut speaks about a world struggling with a faceless, indecipherable intention. A world registered deep down in our unconscious, strange but familiar, unspeakable, which can sometimes find, given that it cannot be formulated, a form to manifest itself.

Martias, sculpting the surrounding wall of the psychiatric hospital where he would starve to death in 1943 like many other psychiatric patients in France leaves us the image of deadly gangue reflecting the double trap – current and archaic – in which he finds himself (fig. 21).

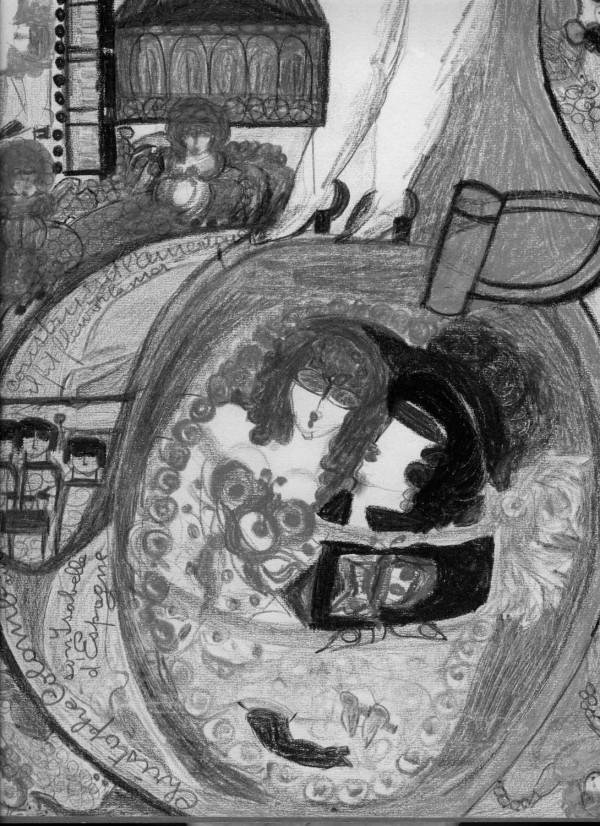

Others organize a system, such as the “new world” built by Aloise (fig. 22). New world in which consistency is based on associative logic that does not care about meaning or chronology.

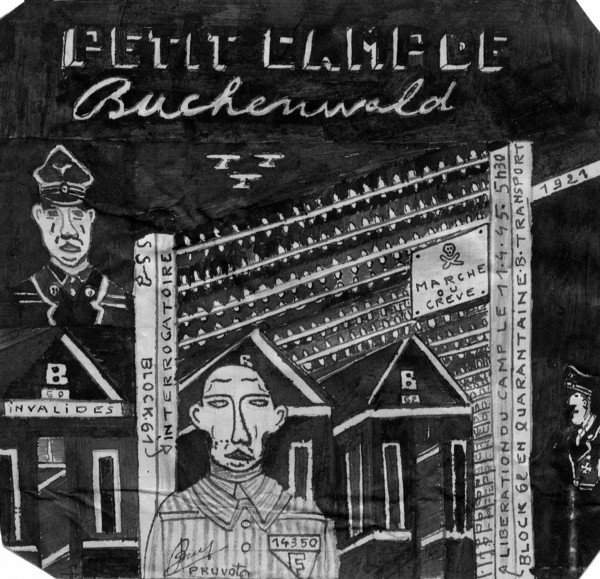

Sometimes there are elements are taken from the culture we all share: something meaningful can find a particular personal resonance. As we would keep from our infancy the idea of malevolence that pursues us, Pruvot links his “little” camp of Buchenwald (fig. 23) to his representation of the “little one” who he used to be.

For barbarism is nothing new: it appeared to us at that immemorial time when the hungry infant assumes the other is as hungry and only sees the terrifying greed in the face yet tenderly leaning into its cradle (fig. 24).

Fig. 1. Serge Sauphar. Untitled, 1948. Gouache on paper, 21 x 27 cm. Inv. no. B352. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 2. Serge Sauphar. Untitled, 1948. Gouache on paper, 21 x 27 cm. Inv. no. B743. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 3. Serge Sauphar. Untitled, 1948. Gouache on paper, 21 x 27 cm. Inv. no. B727. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 4. Serge Sauphar. Untitled, c. 1950. Gouache on paper, 60 x 43 cm. Inv. no. A798. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 5. Serge Sauphar. Untitled, c. 1950. Gouache on paper, 43 x 60 cm. Inv. no. A799. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 6. Serge Sauphar. Untitled, 1949. Gouache on paper, 27 x 21 cm. Inv. no. A914. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 7. Anonyme. Untitled, before 1950. Ink on paper, 24,5 x 9 cm.

Inv. no. A181. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 8. Anonyme. Untitled, before 1950. Ink on paper, 26 x 13,5 cm. Inv. no. A178. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 9. Dwight Mackintosh. Untitled, without date. Colour pencil on paper, 56 x 76 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 10. Anonyme. Untitled, before 1950. Ink on paper, 17 x 11 cm.

Inv. no. A163. Photo Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 11. Dwight Mackintosh. Untitled, 1995. Colour pencil and gouache on paper, 56 × 77 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 12. Thérèse Bonnelalbay. Untitled, without date. Ink on paper, 27 x 37 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 13. Karel Havlicek. Untitled, without date. Pastel on paper, 42 x 29,9 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 14. Scottie Wilson. Untitled, without date. Ink and colour pencil on paper, 40,5 x 30,5 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 15. Attilio Crescenti. Untitled, without date. Ink on paper, 45,5 x 45,5 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 16. Annabel Romero. Untitled, 1989. Ink and felt-tip pen on paper, 21 x 29,5 cm. Inv. no. C669. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 17. Jaime Fernandes. Untitled, without date. Ballpoint pen on paper, 25 x 32 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 18. Rudolf Horacek. Untitled, without date. Colour pencil on paper, 40 x 30 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 19. Annabel Romero. Sans titre, 1990. Felt-tip pen on paper, 21 x 29,5 cm. Inv. no. C690. Archives of la Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 20. Georgiana Houghton. Untitled, without date. Gouache on paper, 48 x 34,8 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 21. Adrien Martias. Sans titre, 1942. Carved rubble stone, 13 x 18 cm. Inv. no. C635. Archives of Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 22. Aloïse Corbaz. Untitled, without date. Colour pencil on paper, 33 x 24,3 cm. Paris, abcd collection.

Fig. 23. Marcel Pruvot. Untitled, c. 1950. Ink on cardboard,

12 x 12,5 cm. Inv. no. C294. Archives of Section du Patrimoine de la Société Française de Psychopathologie de l’Expression et d’Art-thérapie.

Fig. 24. Anselme Boix-Vives. Michel Simon, signed, dated “3.3. 1969”. Ripolin, gouache on cardboard, 70 x 62 cm. Paris, abcd collection.