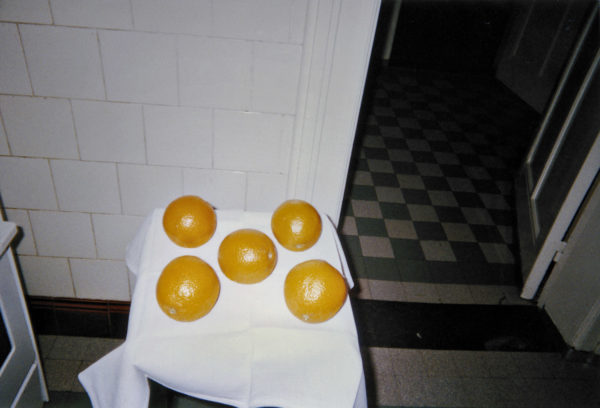

Enfant, Elisabeth Van Vyve est victime de nombreux troubles du développement, d’autisme et de problèmes d’audition qui affectent sa parole ; Elisabeth Van Vyve vie dans sa bulle. Grace au dévouement de sa mère et du reste de sa famille, elle apprend à communiquer par gestes, avec quelques sons et quelques mots. C’est d’abord avec le dessin et l’écriture qu’elle parvient à se connecter avec son environnement. Plus tard elle découvre la photographie qui devient une passion, elle utilise des appareils jetables. Sur une période de 30 ans elle documente le monde autour d’elle de manière méthodique. Le corpus qu’elle a réuni est considérable, des milliers de clichés soigneusement rangés dans de petits albums photo, stockés sur toutes les étagères disponibles de son appartement puis de sa maison de retraite.

A.C.M.

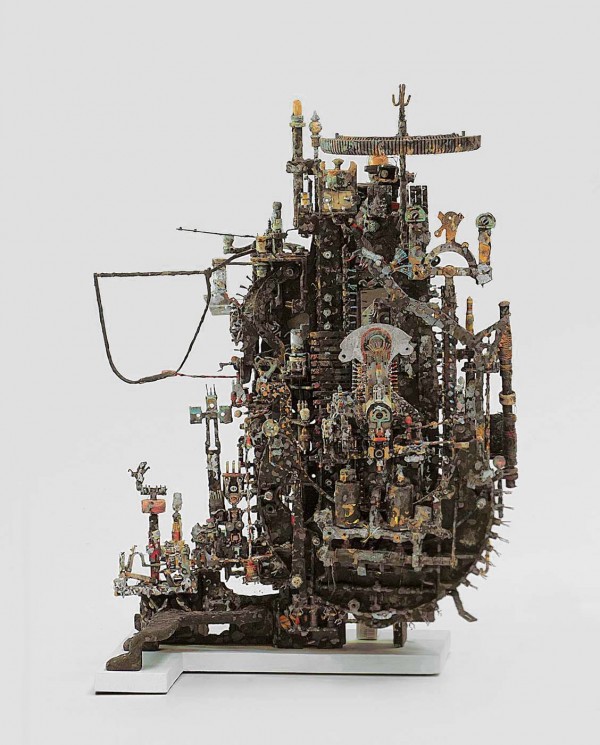

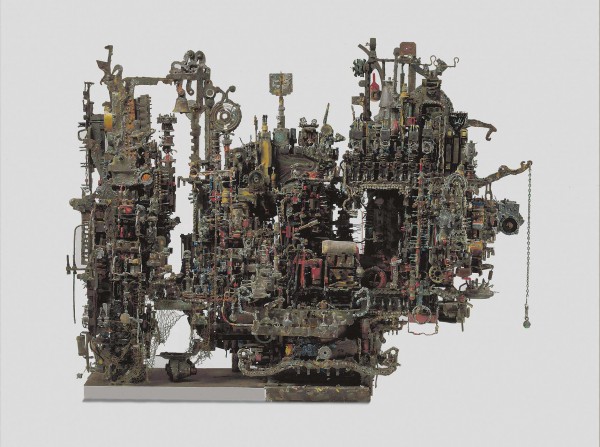

Enfant d’une grande timidité, Alfred Marié s’oriente vers le métier de peintre en bâtiment. Incité par un ami, il entre en 1968 à l’Ecole régionale supérieure d’expression plastique de Tourcoing, qu’il quitte au bout de cinq ans, détruisant alors les travaux qu’il y a réalisés. En 1974, il rencontre Corinne, qui devient sa compagne et un soutien nécessaire à son œuvre ainsi qu’en témoigne le nom d’artiste qu’il adopte : A.C.M. – Alfred Corinne Marié. Au bout de deux ans d’errance, le couple s’installe dans la maison familiale d’Alfred, à l’abandon depuis plusieurs années. Tout en la reconstruisant, A.C.M. reprend son travail artistique et investit l’atelier de son père, un ancien tisserand. Il sélectionne d’abord des pièces extraites de vieilles machines à écrire, réveils, transistors, ou composants électroniques, fils électriques, etc., puis, après les avoir nettoyés, il les métamorphose à l’acide et les oxyde pour les assembler par collage. Il bâtit ainsi des architectures, sortes de cathédrales ou de bateaux, des labyrinthes peuplés de miroirs.