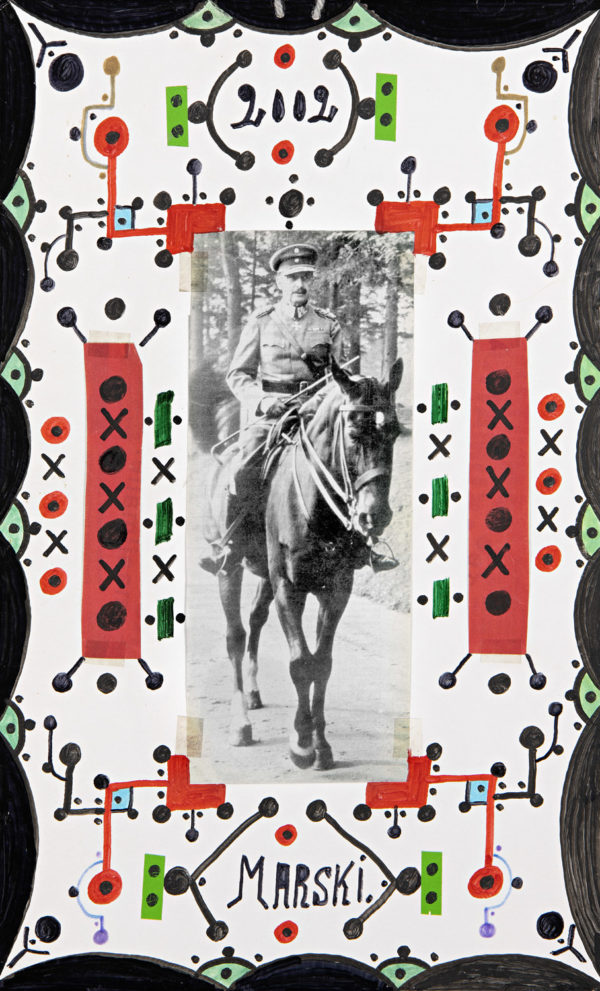

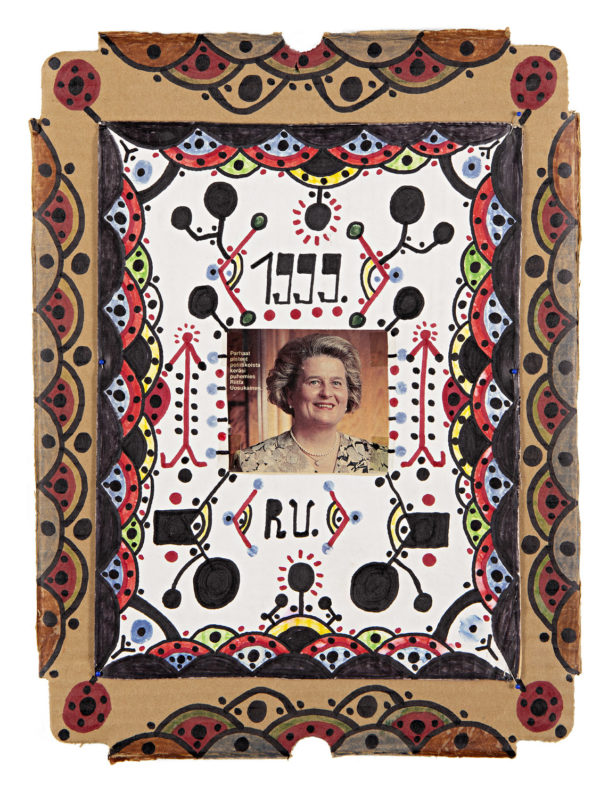

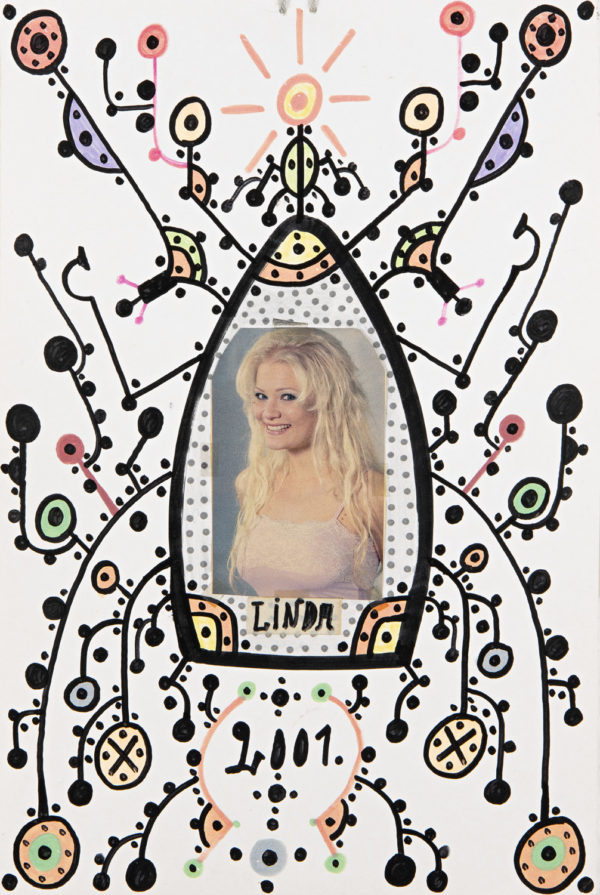

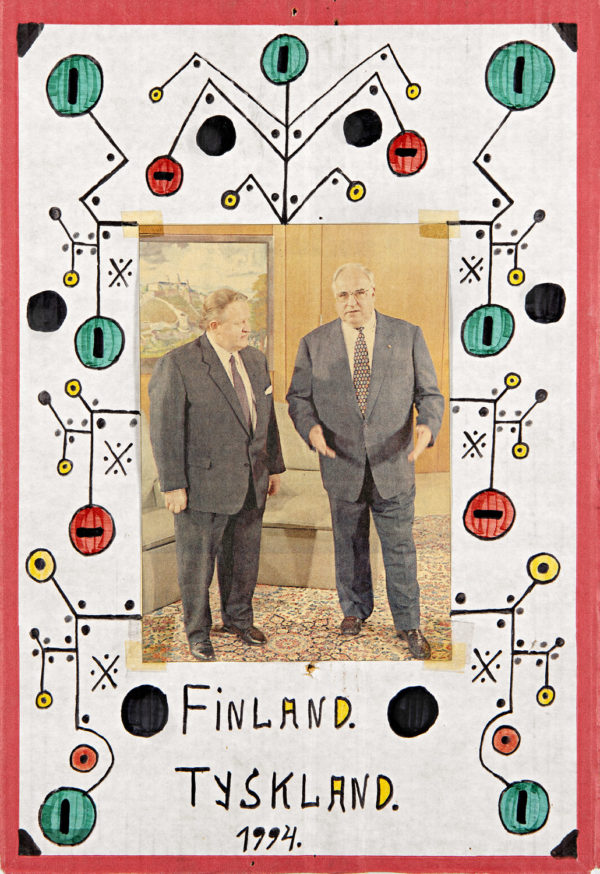

Pendant la guerre, alors qu’il n’a que 14 ans, Ilmari Salminen, surnommé Imppu, déménage d’Helsinki à Petäjävesi, un petit village du centre de la Finlande pour aider son oncle qui possède une ferme. À la mort de celui-ci, en 1986, il hérite du domaine- La retraite venue il s’installe dans les bois dans une cabane en rondins prêtée par un ami forgeron. Il transforme sa petite maison en une sorte de musée, qu’il baptise Imppulandia, bourrée de ses dessins, de ses collages et d’objets collectés : uniformes de l’armée, téléphones, photographies, pièces de monnaie, billets de banque, etc. A partir de 1994, il commence avec assiduité son oeuvre graphique utilisant des photos d’actualité – avec une prédilection pour les membres de la famille royale – des représentations de personnalités politiques, des « peoples », animaux, courses de chevaux mais aussi de paysages et villes de Finlande.

A.C.M.

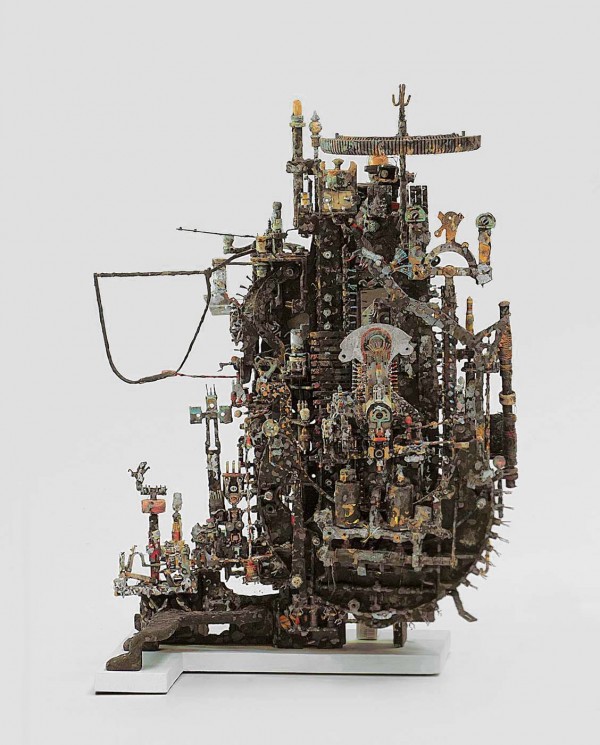

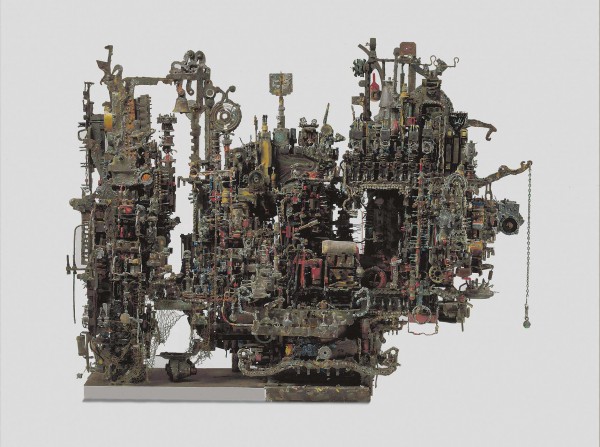

Enfant d’une grande timidité, Alfred Marié s’oriente vers le métier de peintre en bâtiment. Incité par un ami, il entre en 1968 à l’Ecole régionale supérieure d’expression plastique de Tourcoing, qu’il quitte au bout de cinq ans, détruisant alors les travaux qu’il y a réalisés. En 1974, il rencontre Corinne, qui devient sa compagne et un soutien nécessaire à son œuvre ainsi qu’en témoigne le nom d’artiste qu’il adopte : A.C.M. – Alfred Corinne Marié. Au bout de deux ans d’errance, le couple s’installe dans la maison familiale d’Alfred, à l’abandon depuis plusieurs années. Tout en la reconstruisant, A.C.M. reprend son travail artistique et investit l’atelier de son père, un ancien tisserand. Il sélectionne d’abord des pièces extraites de vieilles machines à écrire, réveils, transistors, ou composants électroniques, fils électriques, etc., puis, après les avoir nettoyés, il les métamorphose à l’acide et les oxyde pour les assembler par collage. Il bâtit ainsi des architectures, sortes de cathédrales ou de bateaux, des labyrinthes peuplés de miroirs.