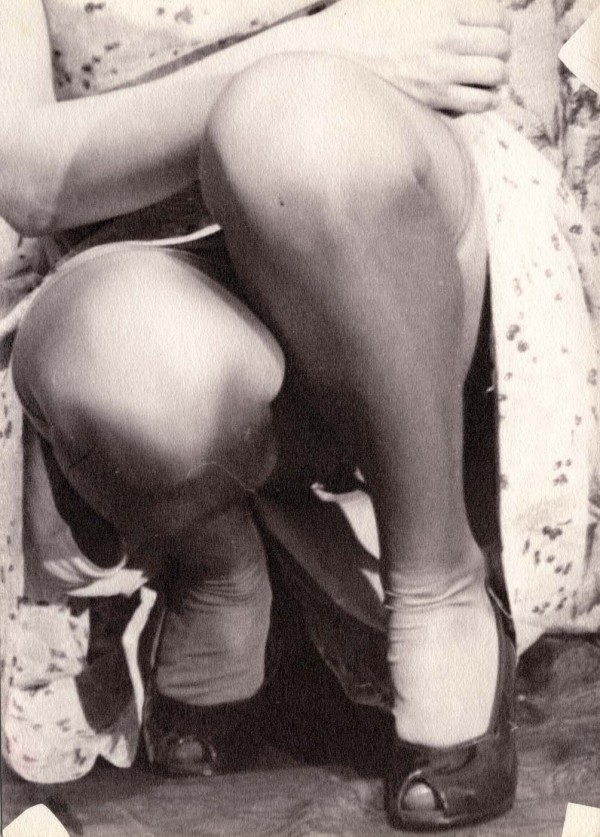

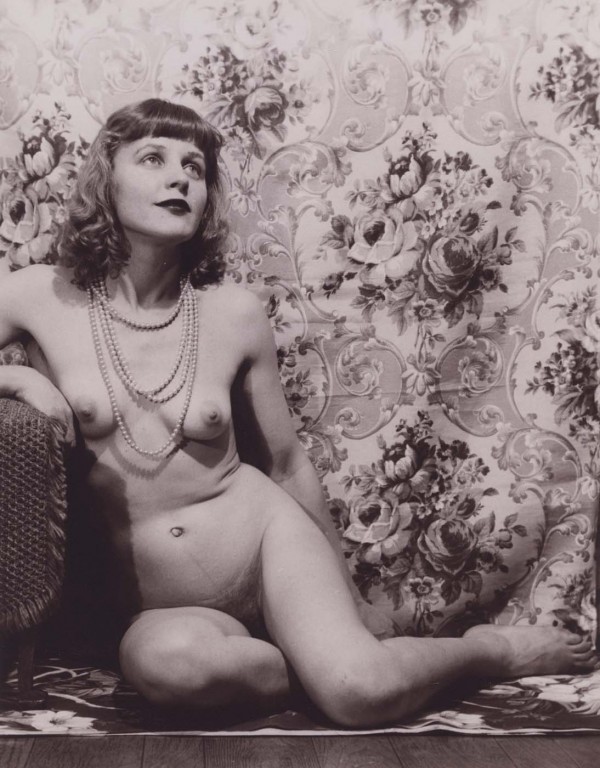

The son of a sign painter, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein dropped out of high school and worked as a florist and baker until the late 1950s. Fascinated by botany and science, he wrote down his metaphysical theories regarding the origins of life, the universe, and genetically coded collective knowledge. He composed numerous poems and devoted himself to painting and drawing. Seeing himself as a pluridisciplinary creator, he engraved his various titles on a kitchen tile: “Freelance Artist—Poet and Sculptor—Inovator [sic]—Arrow maker and Plant man—Bone artifacts constructor—Photographer and Architect—Philosopher.” Von Bruenchenhein created a prolific body of work over a fifty-year period, starting in the late 1930s. Photography, his first consistent practice, began following his marriage to Eveline Kalke—whom he called Marie—in 1934 and continued until the 1950s. He transformed his bathroom into a darkroom to print his black-and-white photographs; he also experimented with double exposures. His wife was the main subject of thousands of photographs inwhich he used various themes, including a pin-up aesthetic, a rococo charm, and tropical exoticism. Drapery, wallpaper, props, and costumes were used for the settings in which von Bruenchenhein gave free rein to his fantasies, enveloping his muse in luxuriant floral compositions with overlapping textures and motifs. Marie’s love for her husband shines through, as do her feelings of naivete, occasional discomfort, and modesty. Over the years, Von Bruenchenhein’s simple home was transformed into a place devoted entirely to art. A nonconformist, he painted in oils with his fingers, fired his clay pieces in his oven, made his brushes with human hair, and recycled chicken bones for his complex assemblages. His studies of clouds and his photographs of Marie—whom he elevated to the status of goddess—are fascinating, as is the reference to his creative spirit named “Genii”—a play on words combining the plural of the word “genius” and the shortening of his first name—who, he claimed, sat on his shoulder and talked to him. When he stopped talking, the artist could no longer create.