I sat in the darkness of the studio, between Bertrand and Jean-Baptiste [1]. A sentence pronounced by Vera Sazhina, whose face appeared in a close-up on the computer screen of the editor, suddenly drew my attention, waking me up from the torpor induced by the semi-darkness of the room, and resonated more strongly than others: “understand where the error occurred.” For several months, we were working with the raw footage provided by Bertrand and other researchers in anthropology who had traveled the world and had brought unprecedented and living words of shamans, sorcerers and exorcists of any kind regarding their “art” (relationship with the spirits, initiation, shamanic cure, trance, etc.) Vera, a Moscow psychologist became shaman in Tuva Republic[2], explained to his interlocutor how she was ‘elected’ by the spirits and what constituted her new role.

“Understand where the error occurred.”

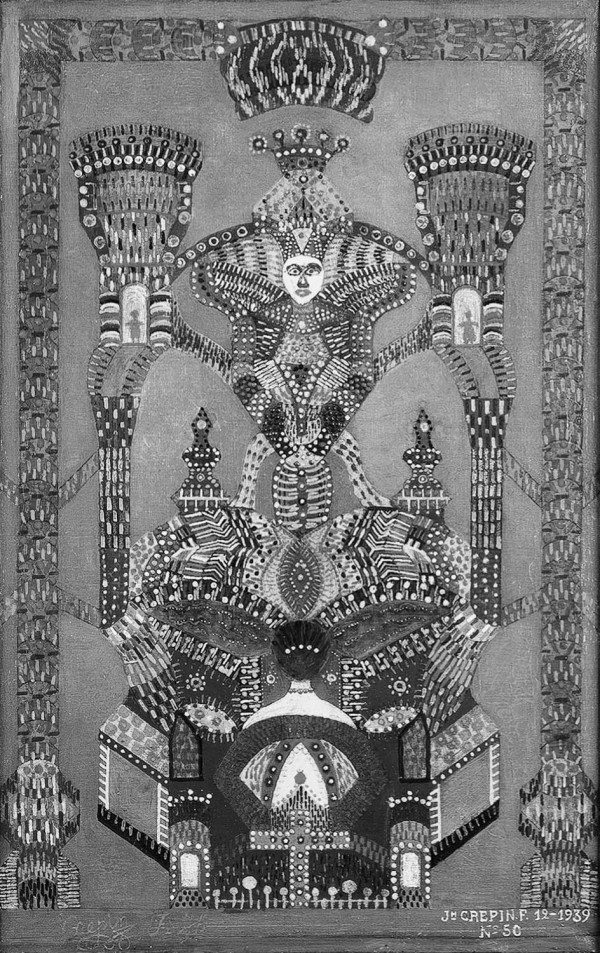

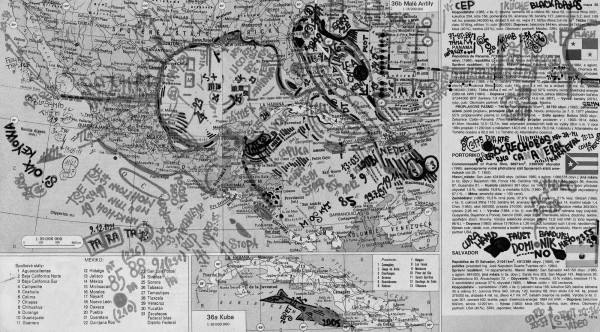

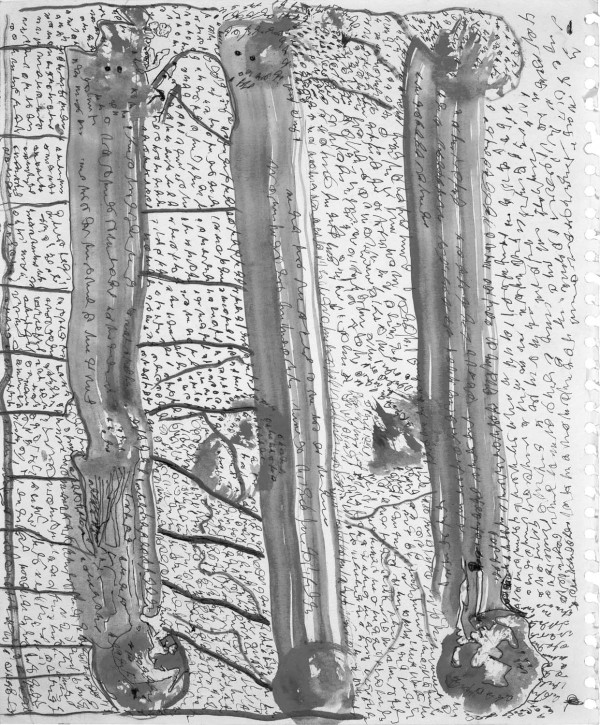

I was not sure to grasp the true meaning of this expression in the context in which it was pronounced; yet it seemed to state a truth and plunged me into thinking, preoccupying me even more intensely later on, when I discovered the works of some very particular artists – namely the creators of the so-called art brut from the collection abcd / Bruno Decharme. Contrary to what I imagined these authors, while producing worlds of their own, and whom I thought tautologically “outside” the ordinary paths of creation, appeared to be very close to what I had observed in certain rituals. Their productions did not seem distant from the magical practices assembled by those respected by their community as healers or revealing messages from the supernatural. I am thinking of Zdenek Kosek, who confided to Bruno Decharme: “My body feels all the universe, I have constant pain in the stomach because there are constantly problems in the universe”, and who was working to transcribe the crucial points into intricate maps, which would contain the chaos: “If I was not trying to solve the problems of humanity, who else would?”; or Adolf Wölfli describing his drawings as “labour”: “You cannot imagine the determination I need to not forget anything”, it seems clear, through these words, that there is something that had been rarely pointed out in respect to these authors, or rather that while it has very often been compared to mystical ecstatic states, it was done without paying sufficient attention to culture. That something, it is an “intention” to repair on the part of these creators of art brut, an intention that does not concern only themselves but the whole society, the whole of humanity.

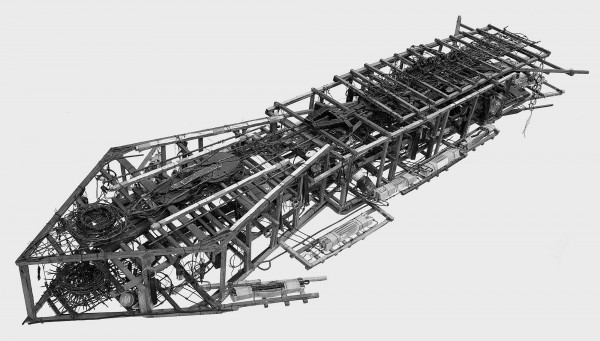

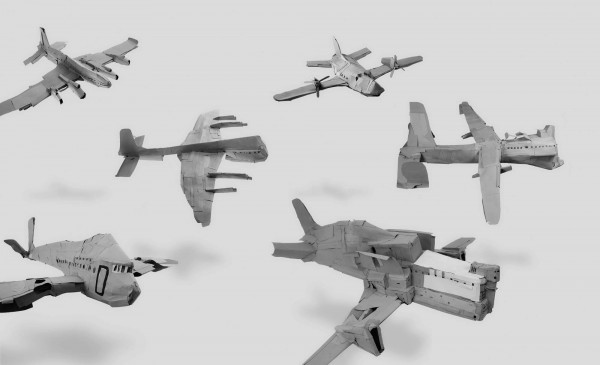

I appeal here to what Picasso designated as the power of art to exorcise, but also to its performative quality. Negotiate with the supernatural, with spirits, name them, such is the task of the shaman to combat anxiety and suffering which – were they meaningless – are potent decomposition ferments. Mastering misfortune is therefore to become familiar with it, integrate it by interfering inevitably in the invisible world. I am thinking of J. B. Murray who, illiterate, reports the words of God in an invented language, only readable in the transparency of a bottle of water from his well; Mary T. Smith who wrote on the roof of her house, her garden fences and any other visible surface, to show her devotion to God; George Widener who is developing a system of numbers with the aim to “keep the world in check”; Hans-Jörg Georgi who has manufactured a fleet of cardboard planes to lead humanity on a journey and touch the sky in order to survive, saying he wants to do “something good for the world”; or Emery Blagdon who assembled in his shed elements of a giant machine for curing diseases; do they not try too, through various media, to ward off the spell? What in my eyes is essential here and falls under real creation, is precisely the intention to “create a work” [3], even more important than the work itself. The work has then the value of a “performative object” or even therapeutic, like Beuys or Tàpies. Create a work is then to locate and limit our personal or collective disorder in the latter: contain the disease in the thread of words, trap the evil between the drawn lines, negotiate the balance of the world by the perilous journey to the dark regions of what escapes us.

“Understand where the error occurred.”

The words of Vera the shaman often come to my mind. By “understand”, she did not really mean that she had to find a solution; rather, she had the intention to circumvent the problem, take it into account, give it a shape, outwit it failing to eliminate it. But the shamanic cure as healing only makes sense if one believes in it. And the active power of art exists under the same condition: the same belief that we grant to the sacred. So it means to believe in the emotional power of creative fiction. Thus, being inspired thanks to the imagination is surely not a flight, or a simple escape, but truly a process necessary for the survival of the world, the active agent that prevents it from becoming frozen, authoritarian and opaque – the guarantee of a vital movement.

[1] I am talking here about Bertrand Hell, an anthropologist invited by Jean de Loisy to collaborate with us on the exhibition “Les maîtres du désordre” [Masters of Disorder], and Jean-Baptiste Delpias, who edited most of the films, les “the words of the initiated”, screened during the exhibition.

[2] The Republic of Tuva is part of the Russian Federation.

[3] “L’œuvre faite compte finalement moins que ‘faire œuvre’” [”The finished work counts finally less than ‘making the work’.”], in Thierry Davila and Maurice Fréchuret, L’Art médecine, exh.cat. [musée Picasso, Antibes], Paris, RMN, 1999, p. 31.