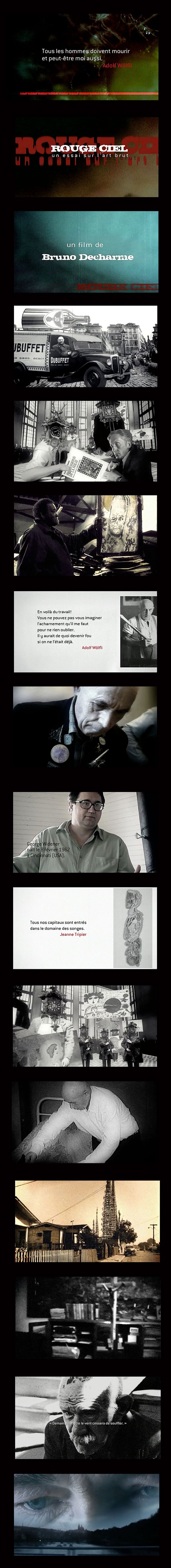

The sky is an angry red, ablaze with voices and faces rolling their clouds of flesh and soul: but is there anger in ROUGE CIEL [Red Sky]? There is certainly a voice – the voice of Bruno Decharme, who offers us this essay, with its clenched fist of a title. And if it contains no anger, why the clenched fist? It’s as if the filmmaker has turned falconer, making this film so that these men and women with their eyes of storm and night, whose flight has fascinated him (and us too) for so many years, should alight here and not elsewhere. And of course the abcd collection provided proof enough of that fascination! Is that why, in this additional role as collector, the filmmaker placed the portrait of Gérard Schreiner at the centre of his essay, as a hidden signature? “I love his “non-standard” career of collector-cum-adventurer and his being a collector-adventurer, and the way he now lives as a Robinson Crusoe “grown wise”(?), is my dream!”, Bruno Decharme tells us.

“ROUGE CIEL”, a title borrowed from Aloïse Corbaz, is thus an “Essay on Art Brut”. It is an almost insane challenge to take the plunge into such whirlpools with a camera – even more than with a pen. There is a greater risk of short-sightedness with the camera trained on the subject – the pen is better at getting the overall picture. And that explains why Bruno Decharme deliberately transforms his camera into a pen. Very much a “written” film, verging at times – as some might rightly object – on preciosity. “It’s a matter of style. Some people go in for factual writing or filming, feeling they have to stay in the background in order to reproduce “the truth” of the subject. Others inscribe what they see and reproduce their emotion. Art brut is an echo of the worlds buried deep within each of us. In order to grasp it you have to plunge into it headfirst without holding back, and let its little story resound.”

There is no comparison between filming Matsumoto, who looks like a child scribe, and Kosek, the prophetic illuminator; not only because the first one is silent while the other is talkative, but above all, because each of them should be shown not as he “is” but as he “inhabits” the world. It is therefore not surprising that Matsumoto’s city, for example, is displayed at first as illegible, scrawled over by speed, like glass by a diamond, seeing that it is by means of illegibility that Matsumoto recounts his world to us. Moreover, the reason why the filmmaker chose to hammer home the date of 20th February 2002 (20.02.02), was to convey in some small way the functioning of Widener’s psychic typewriter. The purpose of the portraits is therefore to provide evidence that art brut is well and truly a place where one can breathe, and not a philosophical category. At this point I recall the extreme close-ups of Widener’s hands: at one and the same time a child’s hands, such as when he seems to be counting on his fingers, and a man’s hands, those of a pianist, pinning his chords onto the great harmonic of the cosmos.

We gladly accept this to be a matter of encounters – and there must have been so much to tell! Moreover, when the filmmaker was asked for an anecdote, he chose his meeting with Lobanov: “Lobanov was brought to me in a very presentable state, accompanied by his warders, who were terrified of any possible blunder. Everything was arranged for a typical official shoot Soviet-style. But this diminutive keen-eyed man in the twilight of his life definitely had something to tell us. That was the day, after all, when he opened the little suitcase that he had kept a closely-guarded secret until then. Permission was for precisely twenty minutes; the film shows ten minutes of it. All these artists that I have filmed – a score of portraits – had no problems about sharing their story. The real problems arose afterwards, when we started to edit. How were we to reproduce the complexity of their worlds?”

Nonetheless, Bruno Decharme seems telling us, the concern to transcribe “his” encounter would fail were other voices not to chip in to show that others had also made this encounter – in their own way: that was the justification for including “testimonies” and for the fact that the director filmed each of those testimonies in a specific fashion, perhaps in order to prove to himself that art brut is not simply a collector’s dream, because others, who are not collectors, also speak about it in terms of a dream.

Consequently the film’s “chief witness”, Michel Thévoz, is the one whose face has been “worked on” the most: he appears to the onlooker, when required, as a sorcerer, or as man, as he says himself, situated somewhere between “madness” – the darkness – and “genius” – the light.

That, then, is the essence of the filmmaker’s style, always ready to bend his camera concertina-fashion, in order to produce a sound most apt for the situation. In this respect the soundtrack plays a fundamental role. Can’t you hear the voice of angels raised in protest? We can, but their vocal cords seem to be the tortured bodies of Darger’s little girls: that is how that voice breaks in this particularly disturbing counterpoint. Conversely, the “owls” from the house of the same name are illuminated by a chanted bestiary. Kosek, for his part, is beaded with black and blue water drops. As we hear them fall it feels like being in a cave, in which we are addressed by this man, more shadow than flesh.

Is there too much talking in ROUGE CIEL? No, the sounds are there to flesh out the image – to give it “volume”. And the camera explores the art works as if seeing them for the first time, as close as possible to their texture, like a robot moving on Mars. Radio-controlled by the eye of the film maker, it captures, shot by shot, a piece of granite from the planet Fouré here, a twig of ink from the satellite Matsumoto there, etc. “This is above all a quest, in search of flavours, tastes, smells, sounds, rhythms, absences, excesses…”

The absence of commentary does not imply the impossibility of finding meaning in these works. The film maker comments on them all the same, by the very fact of pointing his camera at these stars of the first magnitude. Doesn’t art brut seem to be such a star, striking us in the very depths of our mental nights?And of course this star has its history; its genesis is shown in four skilfully-orchestrated sequences; but why use such a nonchalant tone, all too fashionable these days, instead of extolling simplicity – whilst the rest of the film is an appeal for us to discover, i.e. to seek complexity? “A smile is not synonymous with nonchalance. Humour helps us digest History, to render human these “eggheads” who are too often deified. On the other hand, it would be awful if the content of the film were comical.”

Art brut is definitely not to be taken for granted – and let us formally acknowledge that this essay does not employ the unbearable tone of a GPS indicating which route one should take in order to finally understand everything. The expressionist angles, the breathless rhythm, not to mention the anachronistically black, almost alarming, dissolves are the kind of things we expect from a film intended to “enlighten” us; here the intention is not to give the viewer a moment’s respite: the audience must not be allowed to think that this is the last word. As the film proceeds everything that seemed clear is thrown into shadow – an obvious paradox for a medium for which light is vital. So the essay could have reached its conclusion after Darger, whose works open onto the deepest possible mental darkness, thereby displaying its dead end, so to speak. But no it is the portrait of Kosek that brings the film to a close (after the admirable Owl House, to prove to us that people don’t open their eyes as wide as they imagine). We are much more “clairvoyant” than we think – and art brut is only another name for the kind of keen vision that only nocturnal birds possess.

Kosek has the last word – the last word of the film – like a humanist “long pause” in this sometimes gruelling crossing: “I am happy to show [my works] so that people can discover what their brains are able to create.” And the filmmaker corroborates this: “What really fascinates me in art brut is what people are capable of creating.” Ten years’ work went into ROUGE CIEL, alongside the research work of abcd; when asked about its future projects, now that the essay was “printed” and “bound”, Bruno Decharme concluded: “A film about the encounters between gypsy musicians and gadjés – a film about the rejection of ostracism and the richness of cross-culturalism.”