Abandoned by an alcoholic father when he was only seven, Adolf Wölfli was placed as a farmhand and later on, with the death of his mother, sent from family to family. His youth was marked by successive failures in love. Arrested in 1890 for indecent assault, he served two years in prison, but in 1895 he repeated the same offence, this time more serious. Again arrested for attempting to abuse a three-year-old girl, he was diagnosed schizophrenic and committed to the psychiatric hospital of the Waldau, where he remained until the end of his days. Hospitalization marked for him the beginning of a “second life.” Over the first five years, his mental state got worse and he suffered from repeated crises of hallucinations. Around 1900, he began to draw, write and compose music. Dr. Walter Morgenthaler, assigned to the hospital in 1907, became interested in his work and considered him a complete artist, dedicating to him a study published in 1921.

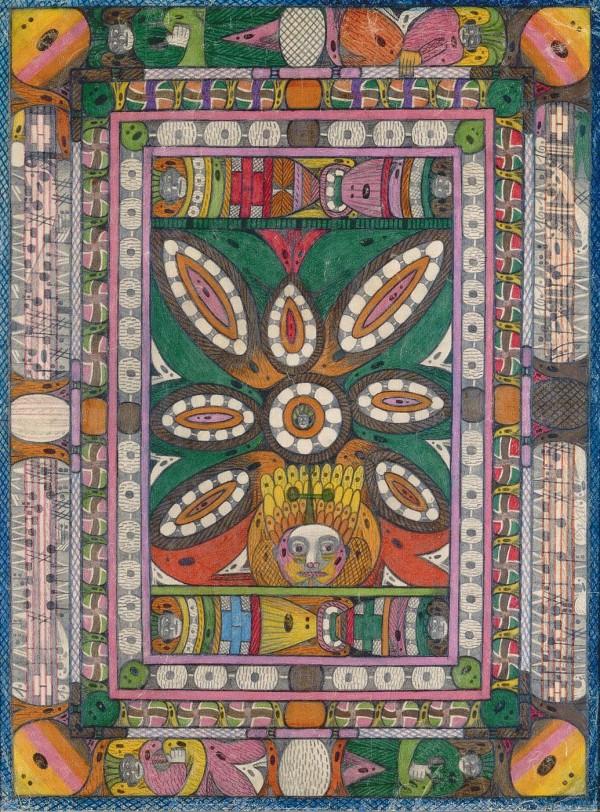

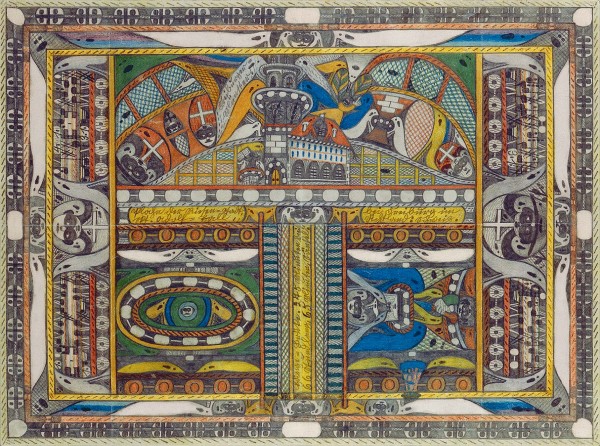

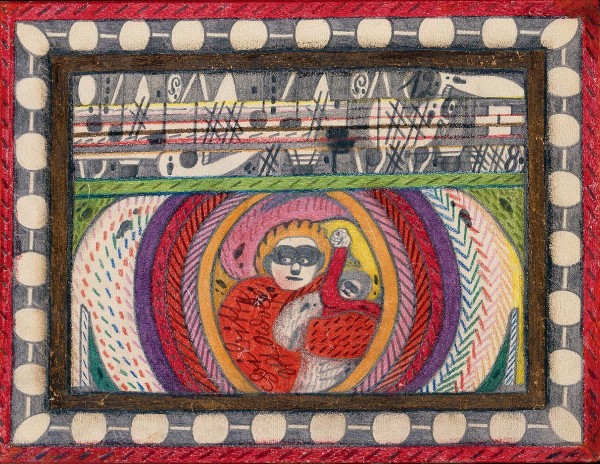

Wölfli’s body of work consists of hundreds of drawings, musical scores, collages and numerous writings forming an extravagant imaginary biography of twenty-five thousand pages. He reinvents everything: history, geography, religion, music, etc. He intends to dominate Creation, Space, but also Eternity. He also excels in pictorial inventions and plays with the superpositions of opposite perspectives: the fusion of several points of view reveals complex networks, where the ornamental elements (staves for example) have a decorative function as well as rhythmic. “Rejected,” victim of a “bitter accident,” Wölfli called himself “Saint,” “Great-Great-God,” “Genius,” or “Adolf II,” “Emperor.” In his world, he escaped all accidents or “attacks by monsters. And if he died, he revives. But he also nicknamed himself “Doufi” — little fellow, lost in a scary world, locked in an endless spiral, lying on his deathbed, in his coffin, the center of a maze. In 1928 he began composing his own Marche funèbre [Funeral March], a requiem of thousands of pages whose composition would be interrupted only by his death.