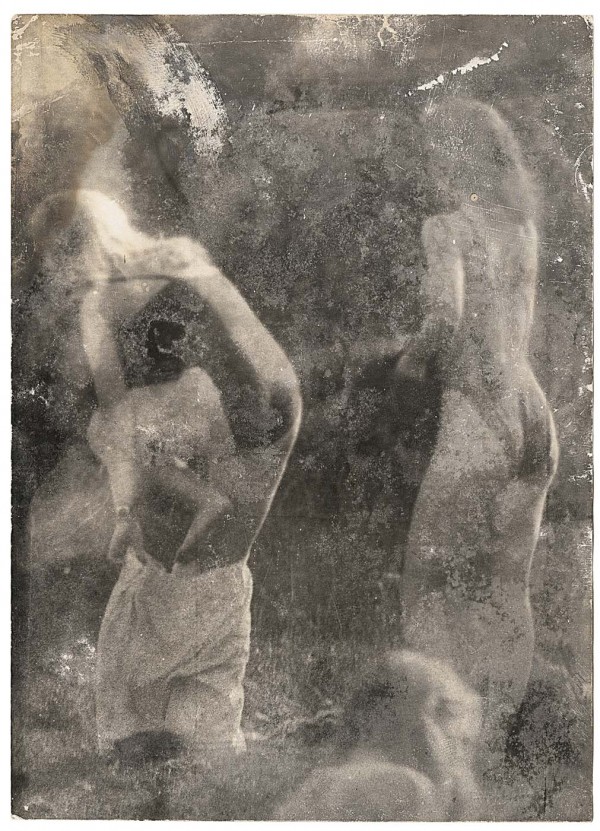

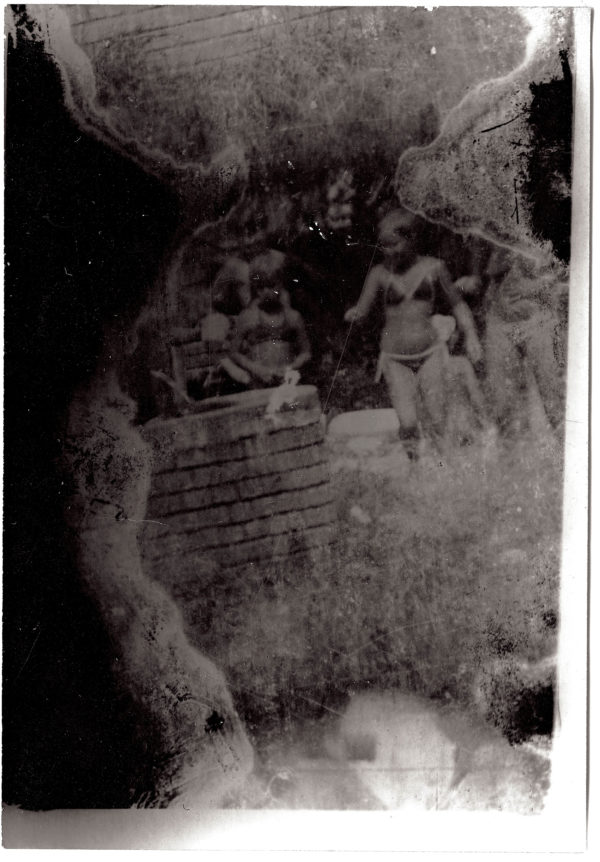

Élève de l’Académie des beaux-arts de Prague, Miroslav Tichy arrête ses études en 1948. Ce peintre plutôt conventionnel, influencé par le cubisme, abandonne dans les années 1970 la peinture pour la photographie – « un nouveau monde » à ses yeux. Il construit lui-même ses appareils photographiques, et, par souci d’économie, utilise de la pellicule de 60 mm coupée en deux. Il réalise ses photographies – des femmes exclusivement, qu’il aborde dans les rues de la ville où il habite ou à la piscine – en dégainant son appareil caché sous son pull, au moment propice, sans jamais regarder dans le viseur, se disant capable, par ce moyen, de « prendre une hirondelle en plein vol ». Il se fixe chaque jour des quotas de clichés. Tirant un tout petit nombre de ses clichés (avec un agrandisseur également fabriqué par lui), les améliorant quelquefois d’un coup de crayon, les encadrant parfois, il abandonnait ensuite ses tirages à même le sol dans sa maison peu salubre, sans les montrer à quiconque. Peu enclin aux règles sociales, étouffantes selon lui, il se clochardise peu à peu. Son appartement, envahi de photos, devient une véritable décharge de son univers. Son travail, découvert par Roman Buxbaum à la fin des années 1990, connut une première reconnaissance internationale grace à Harald Szeemann qui l’exposa à la Biennale de Séville en 2004. Une grande exposition lui fut consacrée en 2008 au centre Georges Pompidou. Pourtant Miroslav Tichy, l’insoumis, ne souhaitait pas que ses photos soient montrées.

A.C.M.

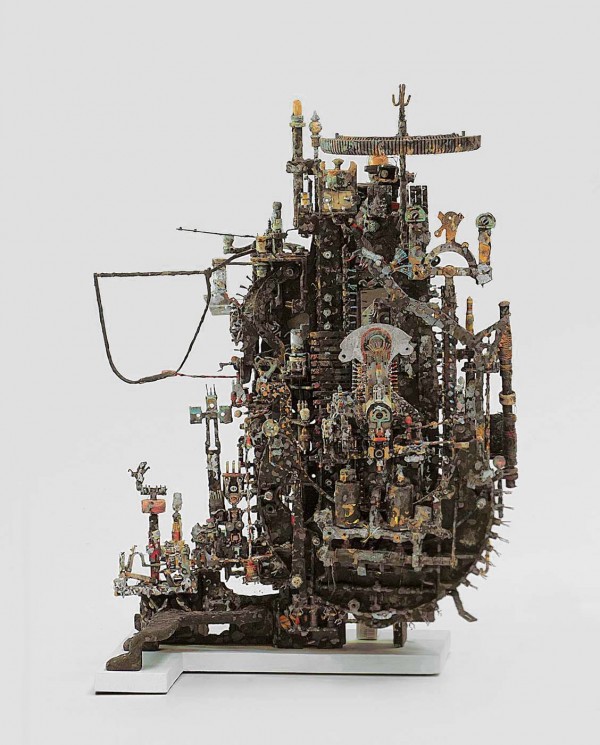

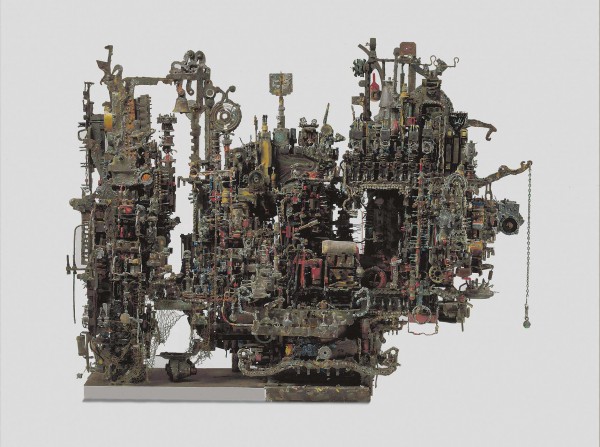

Enfant d’une grande timidité, Alfred Marié s’oriente vers le métier de peintre en bâtiment. Incité par un ami, il entre en 1968 à l’Ecole régionale supérieure d’expression plastique de Tourcoing, qu’il quitte au bout de cinq ans, détruisant alors les travaux qu’il y a réalisés. En 1974, il rencontre Corinne, qui devient sa compagne et un soutien nécessaire à son œuvre ainsi qu’en témoigne le nom d’artiste qu’il adopte : A.C.M. – Alfred Corinne Marié. Au bout de deux ans d’errance, le couple s’installe dans la maison familiale d’Alfred, à l’abandon depuis plusieurs années. Tout en la reconstruisant, A.C.M. reprend son travail artistique et investit l’atelier de son père, un ancien tisserand. Il sélectionne d’abord des pièces extraites de vieilles machines à écrire, réveils, transistors, ou composants électroniques, fils électriques, etc., puis, après les avoir nettoyés, il les métamorphose à l’acide et les oxyde pour les assembler par collage. Il bâtit ainsi des architectures, sortes de cathédrales ou de bateaux, des labyrinthes peuplés de miroirs.